This story was updated at 11 A.M. EDT.

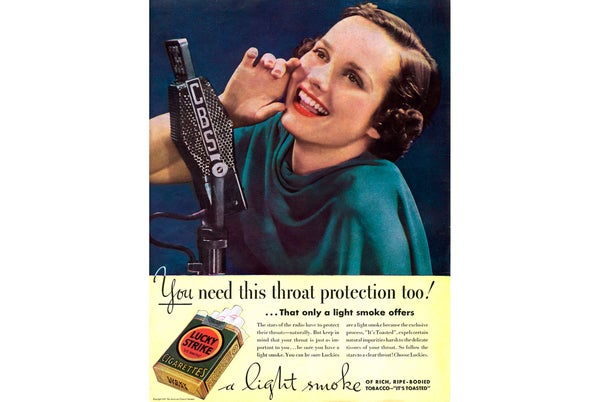

Organizations worried about climate change have long drawn comparisons between the petroleum and tobacco industries, arguing that each has minimized public health damages of its products to operate unchecked.

Some have urged federal regulators to prosecute oil companies under racketeering charges, as the Department of Justice did in 1999 in a case against Philip Morris and other major tobacco brands.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Oil companies bristle at the comparison. But overlap between both industries existed as early as the 1950s, new research details.

Documents housed at the University of California, San Francisco, and analyzed in recent months by the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group, show that the oil and tobacco industries have been linked for decades. The files CIEL drew its research from have been public for years.

The unknown author of one memo, who once worked for Standard Oil Co. Inc. of New Jersey, suggested scientists for an advisory committee study the health effects of smoking.

“I am giving below the names of individuals who you might consider as potential members of the Medical Advisory Committee for the tobacco industry, as related to its current medical problem,” the person wrote to a tobacco research board, alluding to building evidence that smoking caused health problems.

Both industries hired public relations company Hill & Knowlton Inc., an influential New York firm, for outreach as early as 1956.

And Theodor Sterling, a mathematics professor known for research on smoking that was favorable to the tobacco industry—Philip Morris paid more than $200,000 in the 1990s for his work—also studied lead in gasoline for Ethyl Corp. in 1962. Ethyl was a joint venture between General Motors Corp. and Standard Oil.

“From the 1950s onward, the oil and tobacco firms were using not only the same PR firms and same research institutes, but many of the same researchers,” CIEL President Carroll Muffett said in a statement.

“Again and again we found both the PR firms and the researchers worked first for oil, then for tobacco,” he said. “It was a pedigree the tobacco companies recognized and sought out.”

CIEL alerted ClimateWire to the existence of the tobacco documents and has been researching for years what the oil industry knew about climate change and what it did in response.

The examination of the tobacco documents has been more recent for CIEL, which calls its project comparing the tobacco and oil industries “Smoke & Fumes.”

The group’s new research is part of a building debate about oil companies’ knowledge over the decades about climate change. It also is part of a push from environmental groups to make the legal case that fossil energy companies have lied for decades about global warming risks, just as tobacco companies lied about the connection between smoking and cancer.

Last week, House Science, Space and Technology Chairman Lamar Smith (R-Texas) subpoenaed the attorneys general of New York and Massachusetts, who are each investigating if Exxon Mobil Corp. misled investors and the public about climate change threats, and several environmental groups (ClimateWire, July 14).

Smith and his colleagues maintain that the attorneys general colluded with environmentalists in their investigations. They say such probes violate First Amendment protections of free speech.

The Stanford Research Institute link

Another connection between oil and tobacco companies, according to CIEL, is the Stanford Research Institute, now known as SRI International after splitting with Stanford University in 1970.

Founded in 1946, SRI studied smog and pollution generally and received funding from tobacco and oil companies.

SRI scientists also generated climate change research for the American Petroleum Institute in the 1960s and ‘70s.

Spokespeople for Chevron Corp., Exxon Mobil and Royal Dutch Shell PLC said they hadn’t heard of the Stanford Research Institute before, declining to comment further. And API spokesmen did not respond to request for comment.

A blog post from the Independent Petroleum Association of America called the document release a “desperate move” and the latest in a coordinated attempt to hurt the fossil fuel industry.

In a 1968 report prepared for API in New York City, SRI scientists Elmer Robinson and R.C. Robbins acknowledged some uncertainty concerning the relation between carbon emissions and rising temperatures, yet said carbon dioxide was the most likely cause of the “greenhouse effect.”

“If the earth’s temperatures increase significantly, a number of events might be expected to occur, including the melting of the Antarctic ice cap, a rise in sea levels, warming of the oceans, and an increase in photosynthesis,” they wrote.

Robinson followed up in an API-commissioned study dated 1971.

“If there were a long term and significant increase in the pollutant content of the atmosphere either of particles or of carbon dioxide, the potential damage to the global environment could be severe,” he said.

“Even the remote possibility of such an occurrence justifies concern,” added Robinson, one of the first scientists to link the burning of fossil fuels with global warming. He died earlier this year at 91.

The documents show oil companies tested toxicity in cigarettes in the 1950s, and some, including Exxon and Shell, patented cigarette filters worldwide for decades. They also indicate that tobacco companies went to SRI for help in creating small testing kits the size of suitcases to assess smoke.

The Smoke and Fumes Committee

In 1946, API established its own body to study pollution from the oil industry. It was called the Smoke and Fumes Committee.

Wary of government regulation to slash pollution from refineries and other operations within their supply chain, as well as public concern about smog in cities such as Los Angeles, petroleum officials at API and member firms offered alternative theories of how smog was created.

“The worst thing that can happen, in many instances, is the hasty passage of a law or laws for the control of a given air pollution situation,” Vance Jenkins, executive secretary of the Smoke and Fumes Committee, said in a 1954 trade journal article about smog pollution.

The corporate predecessors to Chevron Corp., Exxon Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell PLC were each involved in the Smoke and Fumes Committee through former companies and subsidiaries, often broken-off units of the Standard Oil corporate empire.

While the documents show API learned of potential climate change risks as early as 1968 and had formed committees to examine smog pollution in the 1940s, Exxon CEO Lee Raymond said in November 1996 that climate science was unsettled.

“Scientific evidence remains inconclusive as to whether human activities affect the global climate,” Raymond said at a press conference.

The University of California, San Francisco, documents were cached there starting in 2002 after tobacco industry litigation. Hill & Knowlton references are heavily featured.

An internal Hill & Knowlton memo from 1954 describes a booklet that employees circulated to doctors nationwide on the “cigarette-lung cancer theory.” They also show company founder John Hill, as well as colleagues Bert Goss, Richard Darrow and others, sat in on meetings of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee, an industry panel.

Hill also appears in meeting minutes in the 1950s for the Manufacturing Chemists’ Association Inc. And a flyer from 1963 indicates Goss, president of Hill & Knowlton at the time, hosted an event that November about the future of public relations.

An executive of Socony Mobil Oil Co. Inc., a predecessor of Mobil Oil, coordinated that talk, held at the New School in New York City.

Reprinted from ClimateWire with permission from Environment & Energy Publishing, LLC. E&E provides daily coverage of essential energy and environmental news at www.eenews.net. Click here for the original story.