/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/33271105/olantern.0.jpg)

Presidents consistently overpromise and underdeliver. What they need to say to get elected far outpaces what they can actually do in office. President Obama is a perfect example. His 2008 campaign didn't just promise health-care reform, a stimulus bill, and financial regulation. It also promised a cap-and-trade bill to limit carbon emissions, comprehensive immigration reform, gun control, and much more. His presidency, he said, would be change American could believe in. But it's clear now that much of the change he promised isn't going to happen — in large part because he doesn't have the power to make it happen.

You would think voters in general and professional media pundits in particular would, by now, be wise to this pattern. But they're not. Each disappointment wounds anew. Each unchecked item on the to-do list is a surprise. Belief in the presidency seems to be entirely robust to the inability of any particular president to make good on their promises. And so the criticism is always the same: why can't the president be more like the Green Lantern?

What is the Green Lantern Theory of the Presidency?

According to Brendan Nyhan, the Dartmouth political scientist who coined the term, the Green Lantern Theory of the Presidency is "the belief that the president can achieve any political or policy objective if only he tries hard enough or uses the right tactics." In other words, the American president is functionally all-powerful, and whenever he can't get something done, it's because he's not trying hard enough, or not trying smart enough.

Nyhan further separates it into two variants: "the Reagan version of the Green Lantern Theory and the LBJ version of the Green Lantern Theory." The Reagan version, he says, holds that "if you only communicate well enough the public will rally to your side." The LBJ version says that "if the president only tried harder to win over congress they would vote through his legislative agenda." In both cases, Nyhan argues, "we've been sold a false bill of goods."

Wait, how did the Green Lantern get involved in all this?

The Green Lantern Corps is a fictional, intergalactic peacekeeping entity that exists in DC comics. Members of the Corps get a power ring that capable of creating green energy projections of almost unlimited power. The only constraint is the willpower and imagination of the ring's wearer. There was a long period of time when the ring was ineffective against the color yellow but in more recent comics that's just "the Parallax fear anomaly" at work and with enough courage and willpower, the ring works just fine against the color yellow.

In 2006, Vox executive editor (and then-TPM Cafe blogger) Matthew Yglesias, responding to an argument for bombing Iran, coined the term "The Green Lantern Theory of Geopolitics".

A lot of people seem to think that American military might is like one of these power rings. They seem to think that, roughly speaking, we can accomplish absolutely anything in the world through the application of sufficient military force. The only thing limiting us is a lack of willpower.

What's more, this theory can't be empirically demonstrated to be wrong. Things that you or I might take as demonstrating the limited utility of military power to accomplish certain kinds of things are, instead, taken as evidence of lack of will. Thus we see that problems in Iraq and Afghanistan aren't reasons to avoid new military ventures, but reasons why we must embark upon them.

In 2009, Nyhan, commenting on an argument Yglesias was having with the writer Matt Taibbi, extended the idea to arguments in "which all domestic policy compromises are attributed to a lack of presidential will."

That's the literal answer, anyway. The more philosophical answer is that comics, primarily out of the Marvel and DC universes, increasingly serve as a kind of shared American mythology and so writers turn to them as vehicles for communicating abstract ideas.

What's wrong with the Green Lantern Theory of the Presidency?

Basically, it denies the very real (and very important) limits on the power of the American presidency, as well as reduces Congress to a coquettish collection of passive actors who are mostly just playing hard to get.

The Founding Fathers were rebelling against an out-of-control monarch. So they constructed a political system with a powerful legislature and a relatively weak executive. The result is that the US President has little formal power to make Congress do anything. He can't force Congress to vote on a bill. He can't force Congress to pass a bill. And even if he vetoes a bill Congress can simply overturn his veto. So in direct confrontations with Congress — and that describes much of American politics these days — the president has few options.

Green Lantern theorists don't deny any of this. They just believe that there's some vague combination of public speeches and private wheedling that the president can employ to bend Congress to his will. Ron Fournier, a prominent Green Lantern theorist, offers a fairly typical prescription for presidential success:

He could talk to the media and the public more often with a more compelling and sustained message. He could build enduring relationships in Washington rather than being so blatantly transactional with his time. He could work harder, and with more empathy, on Capitol Hill to find "win-win" opportunities with Republicans.

The problem with this is that the Green Lantern Theory isn't just false. It's often backwards. The basic idea is that more aggressive and consistent applications of presidential power will break down opposition. But political science research shows the truth is often just the opposite.

When the president takes a position on an issue the opposing party becomes far more likely to take the opposite position. In a clever study, political scientist Frances Lee proved this by looking at noncontroversial issues, like whether NASA should try and send a man to Mars. She built a database of eighty-six hundred Senate votes between 1981 and 2004. Typically, these votes fell along party lines just a third of the time. But but when the President took a clear position the likelihood of a party-line vote rose to more than half. In other words, when the president pushed on an issue the opposition party became more likely to oppose him.

The reason is simple: elections are zero-sum affairs. The more the American people perceive the president as successful the less likely they are to vote for the opposition in the next election. "If you're cooperating then it suggests to the public that things are working just fine," explains Lee. "And it undercuts the whole logic of your campaign against the president or the president's party's continuation in office."

The Green Lantern Theory also infantilizes Congress. Take this Maureen Dowd column in which she argues that it's actually the president's job to force Congress to behave, as if the most powerful and democratic branch of the American government is just a bunch of petulant children waiting for discipline:

It is his job to get them to behave. The job of the former community organizer and self-styled uniter is to somehow get this dunderheaded Congress, which is mind-bendingly awful, to do the stuff he wants them to do. It's called leadership.

This kind of thing both lets Congress off the hook and confuses Americans about where the power actually lies in American politics — and thus about who to hold accountable.

But what about LBJ?

LBJ, congressional superhero. (CBS via Getty Images)

What about him? "The LBJ story misses the fact that he had huge majorities in congress at the time he was passing most of his legislation," says Nyhan. "He was benefitting politically from Kennedy's assassination. And the public was unusually supportive of government involvement at that time. If we attribute all those successes to arm twisting then LBJ looks all powerful."

The other problem is that the Washington of the 1960s bears little resemblance to the Washington of 2014. As you can see on this graph of party polarization in Congress, the 1960s were a low ebb:

This was a period in which the Democratic Party contained hardcore conservatives and the Republican Party was thick with Northern liberals. There was so little enmity between the two parties that in 1950, the American Political Science Association's Committee on Political Parties released a report calling on the two parties to sharpen their disagreements so that the American people had a clearer choice when casting their ballots.

Think about that for a second: political scientists thought the problem in American politics was that the two parties didn't fight enough. Can you imagine anyone, anywhere saying that about American politics today?

The middle of the 20th Century was a strange historical moment in which segregation scrambled the American political system. Now that it's over the parties are at war and the minority party knows that their political success is inextricably tied up in the majority party's failure.

It's also the case that many of the tools that presidents and congressional leaders once used to buy votes are no longer available. As Elizabeth Drew writes:

Party discipline has collapsed and even if Obama could promise John Boehner to make his mostly small-town Ohio district into the new Byzantium, Boehner wouldn't be able to extract one more vote from the Republican caucus. Moreover, "earmarks" have been virtually banned on Capitol Hill, denuding senior members of Congress as well as the president of influence they used to have. Budget restrictions and a more vigilant press have made horse-trading almost a thing of the past-or at least far more risky. There's strong reason to doubt that even the mythical LBJ could get a civil rights bill through Congress today.

Finally, there's the simple fact that because the parties have polarized so much and because Republicans and Democrats tend to represent such safe districts it often hurts members of the opposition party to cooperate with the president. Speaker John Boehner and Minority Leader Mitch McConnell's constituents — both in their home states and in Congress — don't want to see them cutting deals with a liberal Democratic president. If they begin cooperating with Obama too often they'll face primary challengers and threats to their leadership positions. This is part of the way the Green Lantern Theory infantilizes Congress. Members of Congress are skilled politicians who understand their political incentives and ideological aims perfectly well. The idea that they're just waiting to be more wined-and-dined by the president is silly.

Why do so many people believe in the Green Lantern Theory of the Presidency?

One reason is that even as the US executive is structurally weak he's perceptually strong. "The heroic narrative of the presidency dominates media coverage," Nyhan says. It also dominates culture. Fictional representations of Washington like the West Wing tend to feature powerful presidents and weak, corrupt congressmen. They also tend to emphasize the power of stirring speeches, as stirring speeches work great on television. Both in fiction and in reporting American politics is a drama that is told through the character of the president and so it's natural that people tend to see American politics as a function of the president's action.

Another reason that Green Lantern theories have been so prevalent in recent years might be that people's perceptions of the president's power were reset during the Bush years. "I think the post-9/11 experience gave people unrealistic expectations," says Nyhan. "It was a very unusual time and people thought that was the norm. It's not often you have both parties lined up behind a president who has approval ratings in the 80s. But I think a lot of people's internal compass was reset by that in a misleading way."

Congress tends to give the president a fair amount of authority over foreign policy, particularly when it comes to war (though even those powers are on loan: it's Congress that declares and finances war). But even in the Bush years, the limits on the president's power were evident: his efforts to privatize Social Security and reform immigration came to naught, for instance, despite an incredibly aggressive push by Bush himself.

Doesn't this let Obama off the hook?

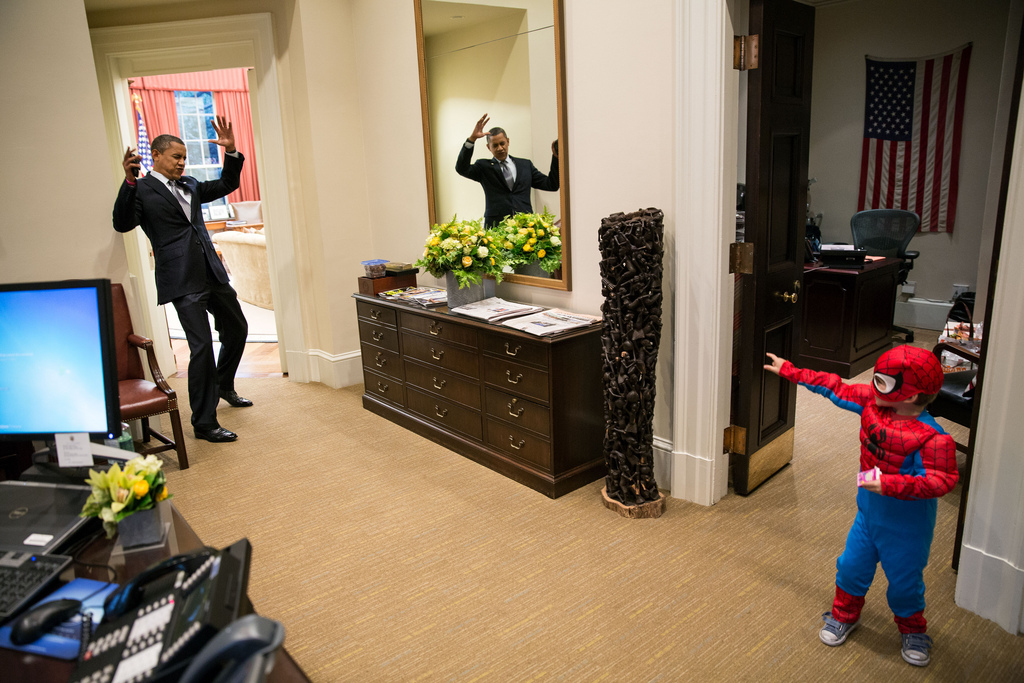

Another way you know the president is not the Green Lantern: the Green Lantern could totally beat Spiderman. Particularly a child Spiderman. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

For what? Not doing things he doesn't have the power to do?

Obama can do a good or bad job within the actual limits of the presidency. The problem with the Green Lantern Theory is that it focuses so much attention on the presidency that it lets everyone else off the hook — and thus makes it harder for voters to hold elected leaders accountable. Outcomes that are actually being driven by Congress, for instance, get attributed to the president, and voters don't know who to blame.

There's plenty meanwhile that is actually up to the president. The Obama administration, for instance, was in charge of implementing Obamacare and they botched it badly. They have a lot of power to set sweeping limits on carbon emissions from power plants and there are real questions as to how they'll use it. They clearly have more power than they've chosen to exercise over the pace of deportations. They now have the ability to push both executive and judicial nominees through the Senate and so the continued slow pace of nominations is on them. The Treasury Department left a lot of money earmarked for helping homeowners languishing in a bank account. Even people without magical power rings can be very powerful:

The executive branch is a big and powerful entity that manages programs of enormous consequence to Americans — and it's often run quite poorly. That's something the president really should answer for. But political reporting in America tends to focus more on new laws that are being pushed through congress than on the implementation of existing government programs. That's a process the president is involved in, but not one, contrary to how Green Lantern theorists portray it, that the president can ultimately control.