Classical economists knew it. But it was only in the latter half of the 20 th century that the link between education and earnings was established in theory and practice. The importance of the earnings benefit of schooling is vital for a variety of social issues. These include economic and social policy, racial and ethnic discrimination, gender discrimination, income distribution, and the determinants of the demand for education. This link between education and earnings is formally made in the calculation of the rate of return to investment in education.

There are literally thousands of estimates of the rate of return to education and several attempts to synthesize this rich literature. In a review of the literature going back 60 years, the lead article in the latest Education Economics is the paper we co-authored, Returns to Investment in Education: A Decennial Review of the Global Literature.” (The free working paper version is available here.)

This paper updates previous reviews on the latest trends and patterns based on more than 1,000 estimates in 139 countries between 1950 and 2014. It summarizes the main findings, and all the data is available online here.

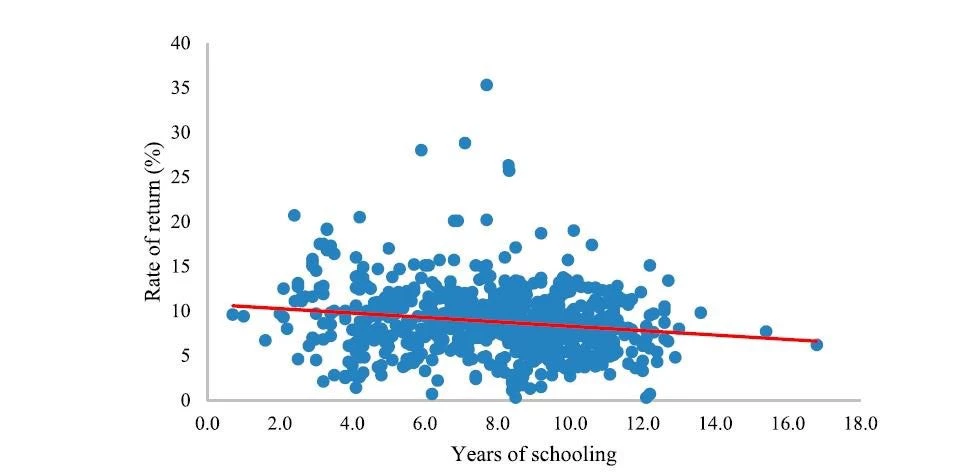

The private average global return to a year of schooling is 9 percent a year

What is interesting is that despite rapid increases in the number of years of schooling, more recent estimates of the returns to schooling have increased. That is, estimates from before 2000 show that average schooling was 7.8 years, and returns to schooling were estimated at 8.7 percent.

However, reviews published since 2000 show schooling at 8.6 years on average and returns to schooling at 9.1 percent. Not a huge increase but bucking the long-term trend and suggesting that the demand for skills is high and might be increasing.

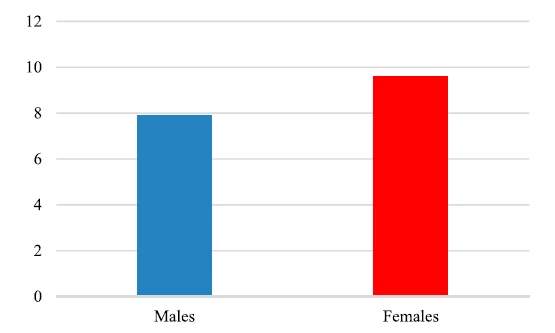

Women continue to experience higher average returns to schooling

This provides yet another reason why girls’ education should remain a priority. Private returns to education for women exceed returns to schooling for men by 2 percentage points, and this gap has increased since previous reviews when the advantage for women was 1 percentage point.

Estimation issues

Typically, returns to education are estimated using the earnings function – which is, simply put, a single-equation model that explains wage income as a function of schooling and experience, which basically means that your labor market earnings depend on your level of education and amount of work experience. The most popular form is the Mincerian earnings function (named after the great economist Jacob Mincer). However, it has been the subject of controversy in the literature. The earnings premium associated with the level of education suggests that productivity increases as people acquire additional qualifications.

An alternative view is that earnings increase with education due to credential effects. This refers to the idea that higher levels of schooling are associated with higher earnings, not because they directly raise productivity, but because they certify that the worker is likely to be productive. In this sense, education merely sorts workers according to their unobserved attributes; it does not necessarily augment their intrinsic productivity.

For public policy reasons it is important to distinguish between the human capital (productivity) and screening hypotheses about returns to education.

- Human capital hypothesis: Schooling imparts skills that enhance productivity. This means that increases in earnings are due to the increased productivity brought about by investments in schooling.

- Screening hypothesis: Employers select workers with higher qualifications to reduce their risk of hiring someone with a lower capacity to learn. In this case, higher earnings may not be due to productivity alone.

Rigorous tests of the screening hypothesis reveal some evidence of weak screening, but overall education is generally associated with higher earnings due to productivity. Brinch and Galloway (2012) exploit a reform that increased compulsory schooling from 7 to 9 years in Norway in the 1960s to estimate the effect of education on IQ. The schooling reform, which primarily affected education in the middle teenage years, had a substantial effect on IQ scores measured at the age of 19. This suggests that schooling increases general ability, casting doubt on the pure signaling model. Also Schneeweis, Skirbekk and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer (2014) find a positive impact of schooling 40 years later on memory scores. The link between education and intelligence is strong, according to metanalyses of quasi-experimental studies. More recent evidence on education’s contribution to intelligence has been shown for Libya and Indonesia.

There is a clear message coming from the above research. Education is a contributor to many beneficial socio-economic outcomes. It is a pity that in many instances it is short-changed in budgetary allocations. The reason is that, whereas the results of building a new bridge are visible within a few years, education benefits accrue over a lifetime – too long a period for many politicians.

Join the Conversation