Proponents of the End of Life Choice say that controls on euthanasia will make it safe for all. But the reality is that euthanasia will be impossible to fully regulate, argues Jannah Dennison.

The End of Life Choice Bill has now made its way through the Committee Stage, and with the issue poised to be put to a public vote in 2020, the question of safeguards has been top of mind.

It’s essential to examine the finer details of any law, especially one such as this. But the bill rests on the assumption that we can control euthanasia; that if we try hard enough, we can prevent both misadventure under the agreed criteria, and the problematic widening of criteria over time.

The reality is, we cannot make euthanasia safe. It is inherently uncontrollable. The detailed safeguards are simply rearranging the furniture when the house foundations have crumbled. Yet many of us so deeply want to make it safe. And so we believe that the wanting will make it possible.

The conditions of suffering for every person are, in fact, so individual and contingent as to make it impossible to draw safe and consistent lines between a person who is eligible for euthanasia, and one who should not be. And the ongoing societal implications are enormous.

Euthanasia safeguards would need infallibly to prevent undiagnosed depression; identify subtle coercion; and consistently identify other underlying factors, such as a deficit in familial, professional, or social support; the fear of being burdensome; or financial concerns. And every one of these factors has been documented – some regularly – as the main reason for accessing euthanasia in overseas jurisdictions.

Safeguards must also prevent any confusion around the difference between assisted suicide, euthanasia, and general suicide, ensuring that no vulnerable person felt that death as a response to suffering had become normalised and thus attractive.

And then we have the clearly documented fact that even tightly prescribed criteria seem inevitably to widen. Which is, of course, a logical progression – and which no legal safeguard can prevent, once you have established the right to die as foundational.

Examples of problems abound. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities stated in April 2019 that she was ‘extremely concerned’ at the impact of the Canadian euthanasia legislation on disabled people eligible for assisted dying, some of whom are being pressured to consider euthanasia.

Take the case of Canadian Roger Foley. Terminally ill, and with associated disabilities, he released recordings of staff offering him euthanasia whilst considering the high cost of his care. Similarly, the mother of severely disabled Canadian Candice Lewis has recounted a doctor’s recommendation of assisted suicide when Candice was ‘dying’ (she did not die, as it turns out), and the accusation that the mother was ‘selfish’ for not pursuing it.

In Oregon, Dr Charles Bentz described a keen sportsman who was diagnosed with cancer, developed depression, and sought euthanasia. Dr Bentz urged caution due to the depression; but later discovered the man had died from euthanasia through another doctor who did not acknowledge the depression. And a 2019 Guardian article told of a Belgian GP, ‘Marie-Louise’, who refused to euthanize a patient who was clearly being pressured by his wife. But when the GP returned from holiday, she found that another colleague had euthanized the man.

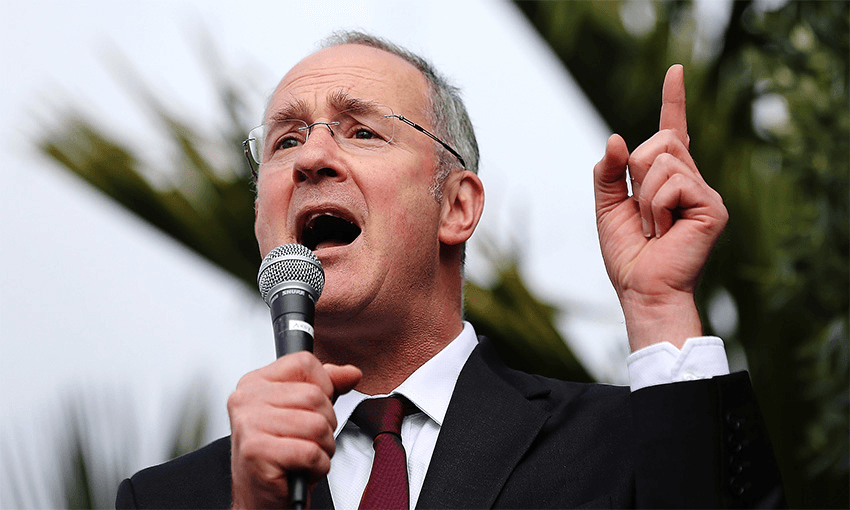

What does Mr Seymour do with such examples? Perhaps, we might say, they are isolated incidents. But even in themselves, do they matter? After all, people have died. At least, do they count as evidence that things can so easily go wrong? And what makes any intelligent person think that these are the only such cases?

Or, you could say: we will be different, with better safeguards. But all of these jurisdictions began with good, painstaking process – why would anyone do otherwise? The impossibility of safety does not finally lie with the process, but the issue itself. When inducing death early, it is naïve to think that nothing will go wrong across all the myriad intricacies of our suffering and our inter-relationships. The problem is people.

Time and again, David Seymour does not sufficiently address specific examples of the problems of implementing safeguards in real life. He comes back to the neatness of things on paper; in fact, he says, astonishingly, euthanasia is “safer than any other process in NZ healthcare”. Why? Because he so much wants it to be safe. And so he doesn’t have an answer to when it’s not.

Professor Theo Boer from the Netherlands – ethicist and former member of a euthanasia review committee – epitomises the discrepancy between the principle and the reality of euthanasia. He doesn’t completely dismiss euthanasia in principle. But he was in New Zealand recently to discuss his about-turn in his advocacy for euthanasia, having seen its uncontrollable complexity in real life: “For years I supported the Dutch law on assisted dying. But… I have more concerns now than ever before… A society’s signal that it is willing to organize the death for its citizens simply involves too many risks.”

Claire Freeman, NZ disability advocate, is the same. “I’ll be honest with you,” she says. “I would love to see people have that choice.” But she too has rejected it; she understands the huge ramifications that euthanasia would have in practice.

So what are we to do?

Given the high confidence of the palliative care sector (who work daily at the coal-face) in the rapid development of good end-of-life care, and given the broad array of medical, legal, and social support organisations in NZ and abroad who have rejected euthanasia, we have only one wise choice. This is to unify our resources and our education towards accessible, quality end-of-life care, and disability and elder support.

Other jurisdictions – over 30 just since 2015 – have faced this question and have chosen against euthanasia, as we should. We cannot introduce a regime that is so inherently uncontrollable. Idealism around our capacity to safely control death will introduce a whole new category of suffering that is impossible to regulate.