These days, studies heralding some promising — or harrowing — new finding about the coronavirus seem to multiply as rapidly as the bug itself. As medical researchers the world over give COVID-19 their undivided attention, each week brings a new smorgasbord of working papers that leave lay observers either jubilantly awaiting the swift reopening of America’s mosh pits or despondently preparing for another 18 months of Zoom dates, depending on which items they happen to sample.

To help you get a better handle on the latest things we’ve learned about the novel coronavirus, and our prospects for vanquishing it, Intelligencer has prepared a brief rundown of all the good and bad news we’ve gotten in recent days.

Critically, just about all of these findings described here are preliminary. Humanity has only had a few months’ experience with the virus formally known as SARS-CoV-2. Our understanding of it is partial and subject to change. So take the following with a grain of salt (but not, under any circumstances, an unprescribed dose of hydroxychloroquine).

The good news.

1) Those who recover from COVID-19 — and then test positive a second time — don’t seem to be infectious.

In recent months, the widely observed phenomenon of people recovering from COVID-19, only to test positive again weeks later, had forced policymakers to contemplate a nightmarish possibility — that humans are incapable of producing antibodies that confer lasting immunity against SARS-CoV-2.

But a new study from the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests that this hypothetical is highly unlikely. The agency’s researchers studied 285 COVID-19 survivors who had tested positive after the ostensible resolution of their illnesses — and found none of them to be infectious. Virus samples taken from the patients failed to grow in a lab test, indicating that the survivors are shedding dead coronavirus. Which makes sense. For weeks now, scientists have been warning that the widely used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests cannot distinguish between the RNA of a live virus, and that of inactive virus fragments that linger benignly in the body long after recovery.

The finding will also allow COVID-19 survivors in South Korea (and likely, elsewhere) to return to normal life sooner after recovery, as the government will no longer require those who’ve had the disease to test negative before returning to work.

2) Those infected with the closely related SARS virus retained neutralizing antibodies for years afterward.

A recent study of people in Singapore who had contracted severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in the early aughts found they retain “significant levels of neutralizing antibodies” for nine to 17 years after initial infection. Since the COVID-19 virus is a cousin of SARS, this finding is another promising sign that humans may develop long-lasting immunity to the former.

3) An antibody discovered in the blood of a patient who caught SARS in 2003 appears to inhibit all related coronaviruses — including the one that causes COVID-19.

This one could be big. Researchers from the University of Washington School of Medicine and Vir Biotechnology say that the antibody they’ve identified, known as S309, “likely covers the entire family of related coronaviruses.” One of the chief obstacles to the development of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine — or potent antiviral — is that the virus is perpetually mutating. But the Vir Biotechnology study suggests that S309 targets and disables the spike proteins that all known coronaviruses use to enter human cells. Which would mean that, no matter how the novel coronavirus evolves, it would “be quite challenging for [the virus] to become resistant to the neutralizing activity of S309.”

For now, S309 has only proven itself to be an effective COVID-19 slayer in lab cultures, and still needs to be tested in people.

4) An experimental vaccine triggered an immune response — and no significantly adverse health problems — in eight human beings.

There is one coronavirus vaccine that has already been tested in humans — and at this early stage appears to be both safe and effective. Or so its manufacturer, the biotech firm Moderna, announced on Monday. In its trial, the first eight participants to receive two doses of the vaccine developed neutralizing antibodies similar to those found in recovered COVID-19 patients. Moderna’s vaccine is of the novel, RNA-based variety — a characteristic that would make the substance safer and easier to mass produce than conventional vaccines. But the novelty of Moderna’s approach also invites some skepticism about its purported results. At present, no RNA-based vaccine has been licensed for use anywhere in the world.

Further, Moderna has yet to make all of the data from its trial available for public scrutiny. And what we have seen is less conclusive than Wall Street wants it to be. While eight subjects did develop neutralizing antibodies, 37 still hadn’t as of Monday (testing for these things can be a lengthy process). The eight that did possess antibodies tested positive for them just two weeks after receiving the vaccine, making it unclear whether the treatment provides long-lasting protection against the virus.

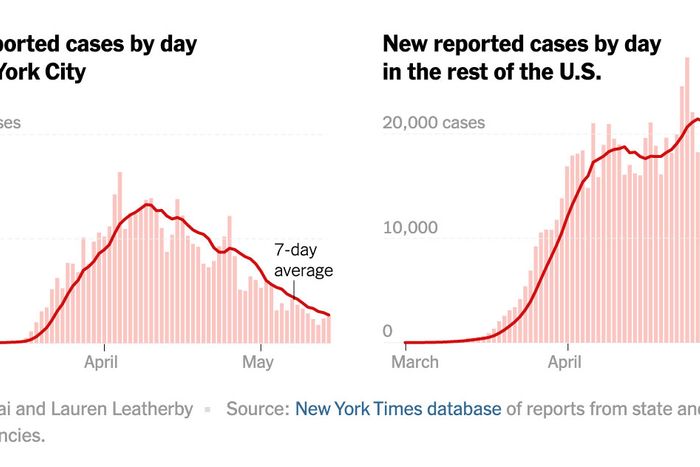

5) After a long plateau, coronavirus cases in the U.S. are steadily declining.

The decline comes as a growing body of research affirms the efficacy of government shutdown orders in containing the spread of the virus — and as a growing number of states relax those shutdown orders.

6) One top coronavirus model has cut its projected death toll for the U.S. by 3,700 (now, it expects “only” 143,360 Americans to die of COVID-19 by the beginning of August).

Last week, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IMHE) model revised its projection for the total number of U.S. coronavirus deaths sharply upward, anticipating a surge in cases following the reopening of several states’ economies. But the latest iteration of the model is a bit more sanguine. Researchers say this is likely because the correlation between the rate of COVID-19’s spread, and increases in human mobility, has proven weaker than anticipated. They hypothesize that widespread mask-wearing and observation of social-distancing protocols may be rendering state-level reopenings less hazardous than anticipated. (This said, it remains too early to draw any firm conclusions from Georgia’s apparently benign experiment with rapidly rescinding shutdown orders).

7) Masks do seem to help quite a lot.

Scientists in Hong Kong recently took a bunch of hamsters, infected half of them with COVID-19; segregated the infected and healthy ones into separate, adjacent cages; and put a fan between the cages to blow particles between them. Soon enough, about two-thirds of the healthy hamsters became infected.

They then ran the experiment again, this time covering the infected cage with mask barriers — and the infection rate among healthy hamsters dropped to 16.7 percent.

So, if you insist on frequenting crowded spaces during the pandemic — and never leave the house without the pet rodent you deliberately infected with COVID-19 — please mask your hamster. (You should also probably wear a mask yourself, even if you leave the house sans rodent.)

8) Your dog (probably) doesn’t need to wear a mask.

The first two dogs known to have caught the coronavirus probably caught the bug from their owners, according to researchers in Hong Kong. Their study produced no evidence that dogs can spread the illness to other dogs or humans, and veterinary epidemiologists doubt that canines are very susceptible to the virus. That said, our knowledge on this subject is limited. So you probably shouldn’t let your dog dine in at restaurants again just yet.

9) Catching a globally dreaded disease, and then becoming so severely ill as to require hospitalization, may have a negative impact on your mental health — but (probably) only temporarily.

A new review of studies on the mental health of coronavirus patients offers the shocking insight that some people with severe cases of COVID-19 experience “delirium, confusion, and agitation” while hospitalized for their life-threatening ailment. Fortunately, the review also suggests that “no longer being at risk of suffocating to death” has a beneficent impact on the mental health of COVID-19 survivors, most of whom do not appear to suffer from mental health problems post-infection. Which I suppose qualifies as good news. Although the upshot of the review (beyond its confirmation of the obvious) is that more research is necessary to determine precisely how prevalent post-traumatic symptoms are in former COVID-19 sufferers.

10) Taking vitamin D may help to prevent your immune system from killing you if you contract COVID-19.

Multiple research teams have found that the patients most sickened by COVID-19 tend to have very low levels of vitamin D, while countries with high COVID-19 death rates tend to also have elevated rates of vitamin D deficiency among their populations. These findings are preliminary. But there is reason to think that healthy blood levels of vitamin D help prevent cytokine storms, in which a person’s immune system overreacts to a coronavirus infection and starts attacking his or her own body’s cells.

The bad news:

1) America is probably much farther away from achieving “herd immunity” than some early studies suggested.

Last month, a pair of very flawed (and arguably corrupt) studies from California suggested that an enormous number of Americans may have already been infected by the novel coronavirus without ever realizing it. This would mean both that the bug is much less lethal than official data suggests (since vast numbers of coronavirus survivors would ostensibly be missing from the data), and that America is much closer to achieving herd immunity than previously assumed.

But that research has since been discredited. And a more methodologically sound study from Spain points to the opposite conclusion: that coronavirus is deadlier — and the American public, father from herd immunity — than experts had assumed.

Spain has suffered a far higher per-capita death rate from COVID-19 than the U.S. or Italy. And yet, its serological testing suggests that only 5 percent of the Spanish public possess antibodies against the novel coronavirus. Which means that there (almost certainly) is not any giant, silent mass of asymptomatic coronavirus survivors in the U.S. — and thus, that we are years (and/or, a mass-distributed vaccine) away from ending the pandemic.

2) COVID-19’s fatality rate appears to be 13 times higher than the seasonal flu’s.

A new study from the University of Washington suggests that 1.3 percent of Americans who are infected with the novel coronavirus and develop COVID-19 symptoms ultimately die of the disease. For the seasonal flu, that rate is just 0.1 percent.

3) Six feet of social distancing might not be enough in certain conditions.

4) Those infected with the coronavirus can contaminate environments before showing symptoms.

In late March, two Chinese students who had no coronavirus symptoms were quarantined in a hotel room for two days. Shortly thereafter, they were both diagnosed with COVID-19. A new study reveals that the students left traces of the coronavirus on several surfaces in their hotel room.

5) A disconcertingly high percentage of people hospitalized for COVID-19 in New York City developed kidney problems.

Between March 1 and April 5 of this year, 5,449 COVID-19 patients were admitted to Northwell Health’s New York-based hospitals. Some 36.6 percent of those patients ended up suffering acute kidney injuries, according to a recent study from the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research. This was the largest study of COVID-19’s impact on kidney function to date.

6) COVID-19 appears to cause serious cardiovascular problems in many patients, and some hypothesized that treatments for the disease exacerbate those problems.

A recent study in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine indicates that between 7 and 17 percent of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 develop myocardial injuries, and that the disease is also associated with heightened risk of heart attacks and stroke-inducing blood clots. Meanwhile, two experimental treatments for COVID-19 — remdesivir and hydroxychloroquine — may worsen the cardiovascular problems caused by the disease.

7) Summer won’t save us.

Most coronaviruses exhibit seasonality, spreading more readily in the winter than in the summer. And there is some evidence that heat, and the summer sun’s ultraviolet rays, do inhibit the novel coronavirus’s spread somewhat. But new research from Princeton University suggests that climatic forces will be of limited help. The reason for this is simple. Other seasonal viruses face a two-pronged challenge in the summer months: They must not only navigate around the heat and ultraviolet light, but also the large mass of humans who boast effective antibodies against them. By contrast, for the novel coronavirus, just about every human is an infectable human. And this near-universal susceptibility does far more to quicken the bug’s spread than the sun does to slow it.

“We project that warmer or more humid climates will not slow the virus at the early stage of the pandemic,” Rachel Baker, a postdoctoral research associate in the Princeton Environmental Institute, said in a statement. “We do see some influence of climate on the size and timing of the pandemic, but, in general, because there’s so much susceptibility in the population, the virus will spread quickly no matter the climate conditions.”

8) Infected kids may be just as good at spreading the coronavirus as adults.

Children face an extremely low risk of developing severe illness from the coronavirus, and account for only about one percent of confirmed coronavirus cases. Some have inferred from this fact that minors are less susceptible to becoming infected by the virus, and thus, less liable to spread it.

But there has always been an alternative possibility: that children are every bit as susceptible to catching and spreading the bug, but simply have exceptionally high rates of asymptomatic infection. And a recent study in the Lancet lends credence to this interpretation. In a study of the coronavirus’s prevalence in Shenzhen, China, researchers found that 7.4 percent of children under 10 had been infected — higher than the 6.6 percent infection rate among the general population.

Other research has produced contrary findings. But since there is no question that small children are not the most hygienic among us, so long as there is ambiguity on this subject, authorities will likely be reluctant to reopen schools and daycare centers.

9) When a person infected with the coronavirus speaks, droplets of virus can linger in the air around them for up to 14 minutes.

Everyone knows that viruses can spread through coughs. But a study published last week in the The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences indicates that the novel coronavirus may travel quite effectively atop human speech. Researchers found that a normal conversation can produce thousands of saliva droplets small enough to hang in the air for eight to 14 minutes.

10) Smoking dank nugs probably won’t make you immune to the novel coronavirus.

Finally — and most devastatingly — reports that smoking weed “may stop coronavirus from infecting people” have been greatly exaggerated. Researchers from universities of Lethbridge and Calgary did publish a non-peer-reviewed study in April that suggested a cannabis-infused throat gargle or mouthwash may inhibit the coronavirus’s ability to enter the body through oral mucus. But that finding was based on applying cannabis extracts to imitation human tissue, not actual human beings. Regardless, the researchers emphasize that even if their findings are accurate, they would not establish any prophylactic benefit to smoking marijuana.

This said, I am aware of small-scale human trials that indicate vaping bud may be an effective treatment for some pandemic-related ailments, such as cabin fever and “being only halfway through Tiger King and already bored.”