Law professor Dr Claire Charters (Te Arawa) lays out Aotearoa’s dual legal systems and the government’s obligations to both in these uncertain times.

The Covid-19 era is like a fast-moving picture which perpetually develops and re-develops. The picture adjusts with ever-changing information on the relevant health-science, the impact on the economy, the need for restrictions on movement, and the openness of our borders into the future. Where does our rock, New Zealand’s constitutional foundation, te Tiriti o Waitangi fit in all of this? Right in the centre, together with He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

First, te Tiriti sets out who has authority to regulate New Zealand, her lands, territories, resources, and the people here. And regulation – in the form of laws, rules and power – is the tool of government to address and respond to Covid-19.

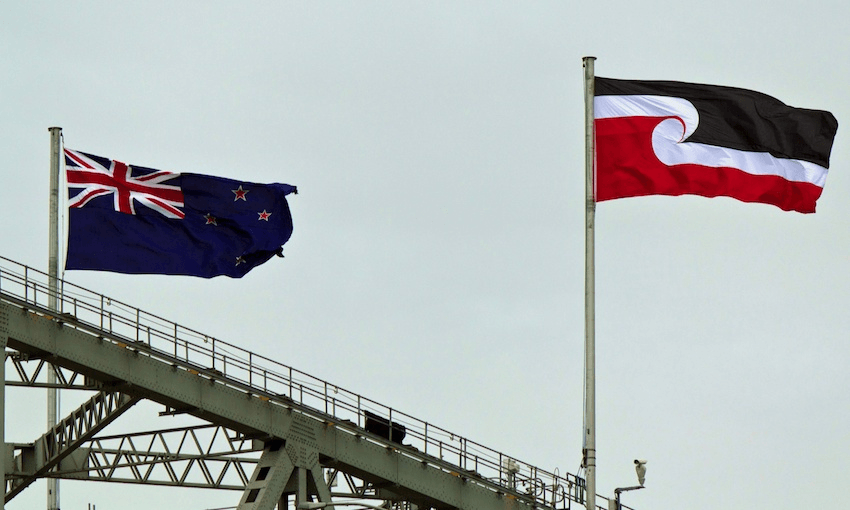

Te Tiriti tells us that the New Zealand state government has some authority (kawanatanga), that Māori have some authority (rangatiratanga), and that state law and Māori law both regulate together. We have seen numerous examples of this. The state has issued new laws and rules under the Health Act 1956, the Epidemic Preparedness Act 2006 and so on. Māori continue to exercise their authority too, under tikanga Māori, to restrict access to our communities, provide flu vaccinations to our people, feed our kaumātua, educate our children, and provide personal protective equipment to our health providers.

As in any place where multiple legal systems are in play – which is anywhere with indigenous peoples – there needs to be coordination between the makers and the enforcers of the law. It has been heartening to see the police and iwi working together on the East Coast and now in Taranaki.

It would be good to see more effort by state government to work in partnership with Māori government to jointly devise and implement strategies, under law, to address Covid-19. State funding to support Māori initiatives to respond to Covid-19 is to be welcomed, even if it might have come sooner. Coordinated governance would be even better, especially based on shared information and expertise.

The UN’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples provides a blueprint for how indigenous law and state law should co-exist. I hope that the New Zealand government will continue with its work towards a plan to realise the Declaration to provide more detail on a post-colonial plural legal structure. We could have used that blueprint during this emergency.

Second, te Tiriti imposes restrictions on state government, te Karauna. If authority and power is not exercised in accordance with te Tiriti or human and indigenous peoples’ rights, it is illegal and illegitimate, even in times of emergency when restrictions can be somewhat relaxed. It is important that both state government, te Karauna, and rangatiratanga Māori are exercised in accordance with those limitations.

The principle of equity is basic to te Tiriti. What we know for sure is that Māori do not enjoy equity with non-Māori in today’s Aotearoa. This is an unfortunate truth in many of the areas that are now under pressure during this time: health, education, housing and criminal justice, especially our prisons.

As my colleague and whānaunga Dr Elana Curtis points out in this excellent piece for e-Tangata, it behoves state government to focus on the impact of seemingly “neutral” Covid-19 strategies on Māori. For example, diverting care from patients with chronic illness which Māori disproportionately experience. And given our relatively high-level of chronic illness, it requires the state to take good care that Covid-19 does not come into high-density Māori communities where the impact could be proportionately worse. Te Tiriti, our foundational law, requires it.

Third, te Tiriti protects Māori rights to taonga Māori, including our culture. How is this relevant during Covid-19? By way of example, it requires attention to how restrictions on movement and association might impact on Māori practising our culture, whether it be in relation to tangihanga and catching fish, or the ability to kaitiaki river or manaaki our manuhiri. Such restrictions, even if part of a general prohibition, are only justified if they are kept to the minimum level and for the shortest time necessary.

So, in this wash of emergency law and regulation needed for the Herculean effort to protect the lives of all New Zealanders from this invidious virus, te Tiriti o Waitangi must continue to be the lighthouse on the shore, guiding our way.

Dr Claire Charters (Te Arawa) is an associate professor of law at the University of Auckland.