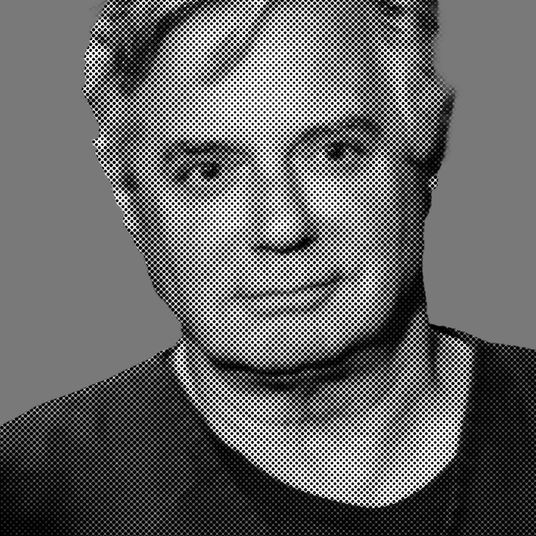

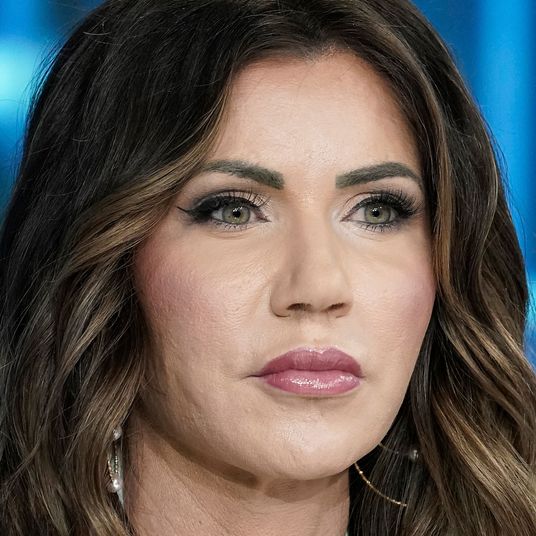

New York City Transit interim president Sarah Feinberg, 42, turns her camera for a moment to show me how deserted the 30th floor of 2 Broadway is. “It’s myself, the guy who sits at the front and lets people through the locked door,” she narrates as she pans MTA headquarters. “A woman who basically runs the office is here some days. And then our NYPD liaison is here most days. And that’s it.” The NYCTA, whose very density has been blamed for New York City being the epicenter of the coronavirus, is being run from a ghost town.

She swivels back to her own nondescript workspace: beige shades, a monitor behind her head, cherry-veneer cabinetry. Feinberg started in the office March 2 — five days before Governor Andrew Cuomo declared a state of emergency in New York — so there hasn’t been much time to decorate.

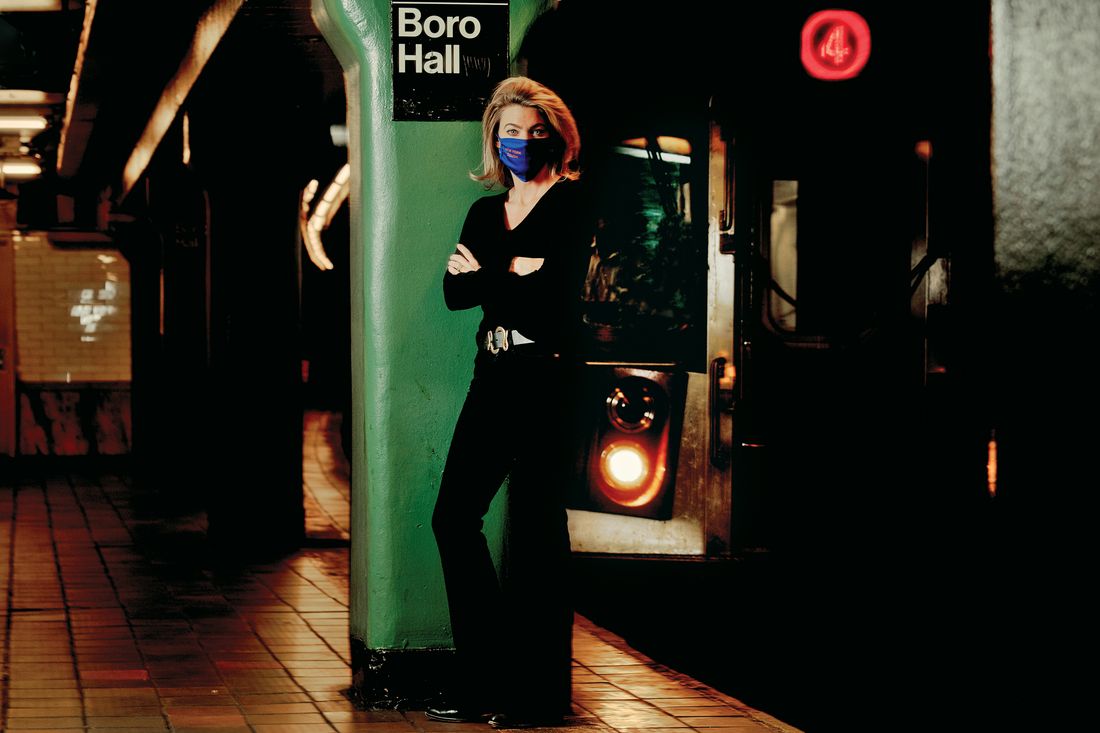

Most days, Feinberg wakes up around 5 a.m. in the East Village apartment she shares with her partner, journalist and former Vice News executive Josh Tyrangiel, and works until their 2-year-old daughter wakes up. (Their nanny has been staying home; Tyrangiel is for now the primary caregiver.) Then she either walks or takes the 4 or 5 to the office on a system where ridership plummeted by more than 90 percent and tries to figure out how to dig New York City’s transit out of a disaster worse than anything anyone has seen before. As of this writing, at least 123 transit workers have died of COVID-19; facing financial ruin, the state-run MTA is panhandling in Washington for its survival; anyone who has a choice is avoiding public transportation, and Feinberg is managing the fallout from an unprecedented overnight closure and cleaning of the trains. There’s a saying in transit that you’re only as good as your last rush hour. But what does that mean when the very prospect of peak crowding is terrifying?

“She is in the most unenviable position of anyone I’ve ever met right now,” says Lisa Daglian, the executive director of the Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA. Does she think Feinberg wants the job permanently? “Oh God, would you? Personally, I don’t know if I would want the job on a good day.”

Feinberg, who ran the Federal Railroad Administration under President Obama and served on Amtrak’s board, actually said “No” a year ago when Cuomo offered her the MTA chairmanship, a rung above her current gig. She’d had a baby and, Feinberg says now, “I couldn’t imagine taking a 24/7 job when she was 1.” Feinberg agreed to be on the MTA board instead, where she made headlines advocating for an expanded transit police force and, less controversially (and less effectively), station accessibility.

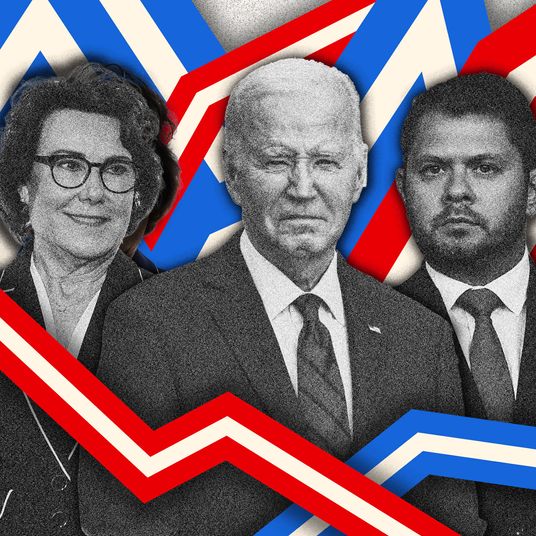

Then Andy Byford, nicknamed “Train Daddy” and adored as incorruptible by the press, transit workers, and advocates, resigned and was regaled by bagpipes and selfie requests. The job, Byford said the week Feinberg started, “had become somewhat intolerable” as he was undercut from above — meaning by the governor. (Byford declined to be interviewed.) On February 23, Feinberg agreed to step in on a temporary basis.

“This is a story about Andrew Cuomo, because every story about the MTA is about Andrew Cuomo,” says the Riders’ Alliance’s Danny Pearlstein. “Andy Byford is not here because of Andrew Cuomo, and Sarah Feinberg is here because of Andrew Cuomo.”

Feinberg says of the governor: “I’ve sat through just countless, countless hours of meetings with him, where I just find that we land on how to address big, deep, complicated knots of problems in a similar way.” And yet even Cuomo critics like Benjamin Kabak, who blogs at Second Avenue Sagas, wouldn’t say Feinberg is simply the governor’s yes-woman. As a board member, Feinberg “wasn’t just parroting what he had to say,” Kabak says. “She was helpful in bridging some of the gaps between Andy Byford and Andrew Cuomo.” Daglian calls Feinberg “no nonsense. She is forceful. She is strong.”

The cautiously warm reception is a testament to Feinberg’s people skills and work ethic, especially considering she only moved to New York in 2017. Or maybe, in a stepchild agency dominated by stagnating feuds between city and state leadership, it actually helps: “She’s not immersed in the past of the MTA and all the prior dysfunction,” said Linda Lacewell, a fellow Cuomo appointee to the MTA board.

The daughter of a legislator and a federal judge in West Virginia (Joe Manchin introduced her at her Senate confirmation hearing and reminisced about meeting her as a five or six -year-old), Feinberg clocked more years in D.C. Democratic politics than in transportation. She spent nearly seven years at the side of Rahm Emanuel, whom she followed from the House to the White House, where she was the senior advisor to Emanuel, who was Chief of Staff. “She doesn’t suffer fools,” Emanuel told me. “She’s willing to walk into an office and tell you when you’re wrong.”

In 2010, Feinberg’s marriage to then-Obama official and current Pod Save America host Dan Pfeiffer ended. She left the White House for blue-chip communications jobs at Bloomberg LP and later Facebook, but told the White House she intended to come back to public service. “I actually just called the White House and said, ‘I’m ready to come back,’” she says. They floated chief of staff at the Department of Transportation or the deputy chief of staff at the Pentagon; Feinberg said she’d be open to either. “I’d love to say it’s this long, simmering fascination with locomotives, but it wasn’t,” she says.

When she eventually took over the railroad regulatory agency, it was a sort of a dress rehearsal for managing through this crisis — major derailments, track fires. Spending the first, pivotal 18 months in the Obama White House had prepared her a bit; she was inculcated by Emanuel’s maxim, which she repeats to me: “I’m a big believer that every crisis presents significant opportunities. Never let a crisis go to waste.”

The question is, an opportunity for what? Not unlike her boss in those early Obama years, Feinberg faces chafing on the left. It started with her stint on the board championing Cuomo’s crackdown on fare evasion (and, she would add, sexual assault on the trains) and to add 500 more cops to the subway. “The policing issue has been a good introduction to the press corps in New York for me,” she says wryly. “I’ve tried to be really clear in how I talk about it and why I think it’s important, and I’m not sure I’ve ever been comfortable with the way I then read it.” She says it was important to have a police force whose priorities the MTA could enforce. When I ask about a video of cops at the Barclays Center station wrestling a woman to the ground in front of her child for not wearing a mask, she says, “Now, if the police are reporting to me, am I going to suggest anyone be arrested for not wearing a mask? No, of course not.” (Mayor de Blasio has since said no one else will be arrested or ticketed for not wearing a mask.)

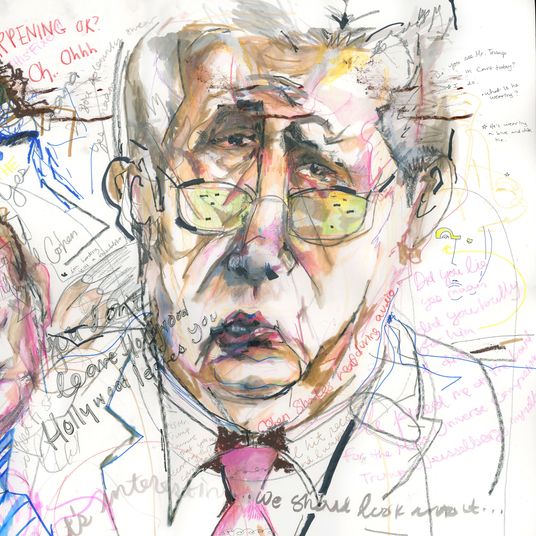

Only weeks ago, MTA workers weren’t even allowed to wear their own masks, following CDC guidance that mask wearing was ineffective. (Tramell Thompson, a subway conductor with a YouTube channel called Progressive Action, titled an April episode referring to MTA chairman Pat Foye “The Inaction of Foye & Feinberg Has Lead to 47 Dead MTA Employees.” It featured a prerecorded condolence message turned pep talk from none other than Andy Byford.) I ask Feinberg, who calls herself “a believer in government,” if she has any regrets. She says, “I deeply regret that the federal government failed on that, so dramatically, for so long.”

Soon after she started, as positive cases and exposures mounted, Feinberg had to decide which workers to quarantine and where to reduce service. She ended up having to self-quarantine when a slew of top managers — her boss Foye, the agency’s chief safety and security officer, and the deputy chief of the MTA police — tested positive. And as executives worked from home, workers on the ground were sidelined — at one point, the entire 2 line was out because its crew had been exposed to a single person who had done fitness-for-duty checks on all of them. Absences inevitably led to service cuts which led to crowding.

“I felt like anyone can take a photo of one car and post it on Twitter, and that’s my New York Post and New York Daily News story that day, right?” says Feinberg. “It may literally be the only rail car on the entire train that’s crowded … but that’s driving my day. Which is frustrating to me.” On April 7, a group of transit and community-organizing groups went further. “Our organizations are alarmed that crowding on particular MTA bus and train routes poses an imminent public-health threat to New Yorkers, especially black and brown communities where the city’s essential workforce is concentrated,” read their open letter.

Feinberg was furious and took what the advocates said was a systemic claim as a personal charge of racism. “I am personally, deeply offended by the suggestion that I, or anyone working for me or with me, would in any way discriminate,” she wrote in an emailed response that I saw, which she asked to be shared with all of the groups. “You do not know me well yet, and you certainly do not know me well enough to suggest that I would allow this to happen on my watch. I hope in time you will know me well enough to know that any form of discrimination is anathema to who I am and everything about me.”

She’s still furious when I ask her about it. “I thought it was absolutely outrageous, unfair, and appalling. To have someone in the middle of a crisis write us a letter saying, ‘No. 1, you’re not doing a good enough job in the middle of a devastating crisis. And No. 2, we think the reason you’re not doing a good enough job is not because this is a massive global pandemic and not because our federal government has failed and not because there’s a whole issue with who are essential workers … but because we think you don’t care about certain people as much.’ Clearly I’m not over it. I’m not getting over that one.”

She maintains New York City Transit didn’t need to be told to redistribute service to essential workers. “There’s a whole advocacy world that makes a living off of weighing in on how we’re doing our job,” she says. “And they fundamentally don’t understand how we do our job. They fundamentally don’t understand that everyone who works here wakes up and tries to figure out how to serve the Bronx.” (Mary Dailey, director of advocacy and organizing at the TransitCenter and one of the organizers of the letter, responded, “Calling on the MTA to think more comprehensively about mobility and racial equity is not a personal attack on any individual or previous efforts, it’s a straightforward recognition that what we have all been doing is broken and needs to be fixed.”)

Conversely, Feinberg is rankled that the head of the New York City Stock Exchange said that employees could come back as long as they don’t take public transportation. “Did you see that?” she says heatedly. “They didn’t say, ‘You’re not allowed to come to work if you go to an unauthorized party in Greenwich.”

The problem for the MTA is that it’s not just stockbrokers who are loath to board a train. In a poll by the research company Elucd, 44 percent of New Yorkers said they plan to avoid public transportation even after lockdown is lifted. The most visible move so far has been to close the subway between 1 a.m. and 5 a.m. for cleaning, even though the CDC is now deemphasizing the risks of surface transmission. Feinberg freely concedes that closing is also about psychological reassurance for potential riders. “People need to know that we’re cleaning, but they need to see that we’re cleaning,” says Feinberg. (Conveniently, the closures, which advocates like Kabak worry will kill 24-hour service forever, also provided the MTA a lever to eject the homeless population from the train.) The MTA is also experimenting with using UV lights for cleaning.

Most epidemiologists agree that sustained contact in closed spaces is prime spreading territory, but decrowding the trains is a lot harder than hiring contractors to spray down cars. Feinberg has been encouraging “the business community” to continue telework or stagger the days of the week employees are expected to be in the office and, barring that, to be more flexible with latecomers whose commute is disrupted because they’re avoiding crowds.

Pat Foye also floated the idea of a reservation on the train. “I think when I first heard it, I couldn’t figure out how it was going to work, but the longer I’ve spent thinking about it, the more I think it has real promise,” says Feinberg diplomatically. For example, rather than reserving a particular train departure, she says, riders could reserve time ranges that would help the system make decisions about capacity. Or, she says, there could be an app telling you which cars in a given train are at capacity.

Though a few Upper East Side stations now have markers on the platform floors to indicate social distancing, Feinberg is pretty blunt in calling the six-feet-apart standard unattainable. “It’s not possible in New York City,” she says. A ridership drop of 90 percent, she points out, still meant 400,000 riders a day, and in recent weeks it’s started to slowly tick up When a routine disruption, like a rail defect, delays the next train, “you have a crowding issue like that.”

A refusal to bullshit her way through the crisis may be Feinberg’s strongest asset. “The most important piece of this job at this moment is to be extremely straightforward and candid with New York about what the system is right now, what it can be, and what their expectations should be.” She is similarly uncoy when asked about whether she’ll stay in the job longer than whatever “interim” means.

“I don’t find the job workable with the way that I want to be a mom and a partner on a permanent basis,” she says. “This is the best job in transportation. It is interesting. It’s exciting. It’s fascinating. It is super-challenging. It will push you harder than you’ve ever been pushed and make you grow in ways that you never thought you would grow, right? And that is the kind of job I yearn for and want desperately. But it is not a 40-hour-week job. You’re not doing taxpayers service by spending 40 hours a week on this job. And you’re not doing your workforce a service. So you’re letting someone down, and I am not at this moment willing to let my family down like that.” Unless, she adds, a little more coyly the job changes somehow.

*A version of this article appears in the May 25, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!