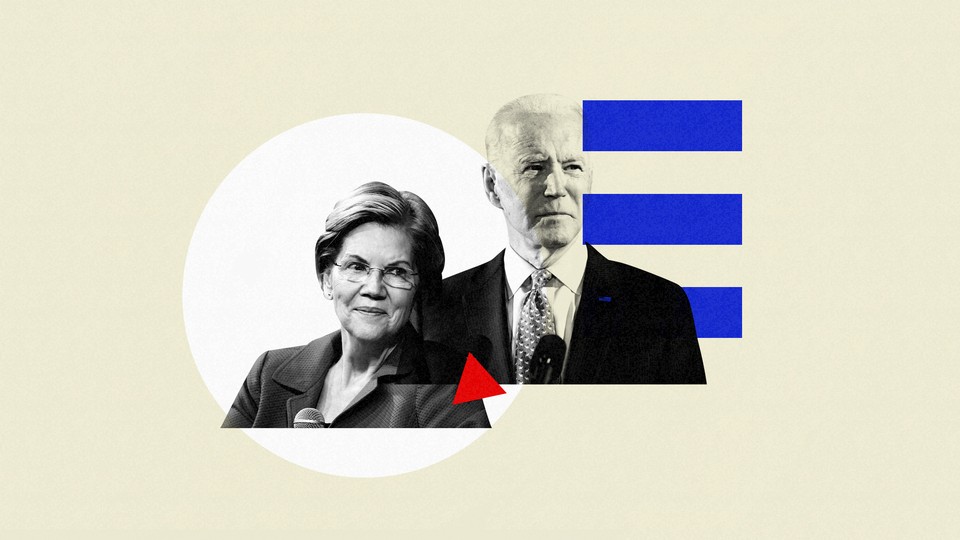

It Really Could Be Warren

After her swing and miss at the presidency, the Massachusetts senator is making a case for herself as Joe Biden’s vice president.

The coronavirus has transformed Joe Biden's campaign, and his search for a running mate. And it has transformed Elizabeth Warren's chances of being picked for the job.

The Massachusetts senator and the former vice president don’t have much of a personal relationship. She was determined to run for president by swearing off big donors; the first event of his campaign was a high-dollar fundraiser at the home of a top executive at one of the country’s biggest corporations.

But this is now a world where the Dow Jones is staying high while the lines at food banks keep getting longer, a world that will be defined for years by the pandemic and its aftershocks. And the presumptive Democratic nominee needs to think seriously—and be seen as thinking seriously—about what comes next.

Suddenly, the senator with all the ideas about remaking the economy seems enticing to the Biden team and it is looking seriously at picking her, according to people familiar with the campaign’s thinking. And suddenly, the senator with all the ideas about remaking the economy is enticed, and thinking seriously about what the job would entail, according to people who described her own thinking on the subject—and according to Warren herself, in two conversations I had with her recently.

“Joe Biden describes this [election] as the battle for the soul of the nation. He’s right,” Warren told me, over the phone from her home in Boston. “But there’s more. It’s the battle for the survival of a nation that works for most of its people or only for a thin elite at the top.”

Put her on the ticket to generate the excitement Biden needs, people advocating for Warren’s selection say, and then prioritize the coronavirus recovery by putting her in charge of it. The candidate who made her whole brand “I have a plan for that” versus a government that seems constantly unprepared—what could be a better contrast?

It’s hard to remember how clearheaded Warren was about the pandemic. She put out her first COVID-19 plan at the end of January, a few days before the Iowa caucus. She was going to roll out more ideas for how to handle the approaching crisis a few weeks later, at the February 19 Las Vegas debate and a CNN town hall, but scrapped those plans in favor of going after Mike Bloomberg. Then, in the first week of March, she warned that the coronavirus would require a $400 billion stimulus response (this was as Larry Kudlow, President Donald Trump’s top economic adviser, was claiming that the pandemic wouldn’t “sink the economy”; today, the stimulus is already north of $2 trillion). But that same week, she was beaten so soundly on Super Tuesday that she came in third in her home state. She quit the presidential race two days later.

When she headed back to the Senate to work on the COVID-19 relief bills, Warren was looking for a way to influence the process. But she didn’t have any sway with Senate Republicans, or much of a relationship with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. So she started making calls—including to Joe Neguse, a not so well known House freshman who was elected by his fellow freshmen as their representative on the leadership team.

She called Neguse’s cellphone and left a message with some thoughts on oversight for the money the federal government was shoveling out the door. He called her back and gave her some insight on the negotiations. They continued exchanging messages. That’s how she proceeded: making lots of calls, strategically identifying power centers and sources of information. One phone call with Biden in March has since become a regular check-in.

Sometimes, she’d quietly mention that her older brother Don Reed Herring was alone in an Oklahoma intensive-care unit, dying of COVID-19.

As the political conversation shifted to who would be the right partner for the massive undertaking that would now define a Biden presidency, people in and around the Biden campaign thought of Warren. The Simpsons “predicted Donald Trump, and they predicted that Lisa Simpson was going to be left cleaning up the mess,” said one Biden donor, referring to a 2000 episode in which Lisa sits in the Oval Office and tells viewers that her administration has “inherited quite a budget crunch from President Trump.” “If I look for someone to compare Lisa Simpson to, it’s Elizabeth Warren,” the donor added. “Now there’s clamoring for her point of view and her personality being a part of the conversation.”

Or take Democratic Senator Tom Carper of Delaware. Warren and Carper aides worked together early in the pandemic on a plan to demand answers about Jared Kushner’s shadow coronavirus taskforce and its Ferris wheel of conflicts of interests. But given his own politics and Delaware’s industry of banks and tax shelters, Carper acknowledged that his partnership with Warren makes for “an unlikely coupling.”

And yet: “If she can put up with me, they can work together,” Carper said of a Warren-Biden ticket. Carper has known and served alongside Biden since they were local Delaware politicians in the 1970s. The two men are close. “He could do a lot worse” than Warren, Carper said. “I’m not sure he could do a lot better.”

For all his campaign’s announcements about a running-mate “search committee,” everyone involved assumes Biden’s final decision will come down to a conversation with one person: Barack Obama.

So what does Obama think? He’s intrigued by the idea of Warren, multiple people who have spoken with him recently told me. Obama and Warren chatted a few times while she was running; she was one of several candidates he called periodically. But the relationship was never that deep or personal, and there was lingering tension from the idea, held by some in his circle, that she wasn’t a team player while they were working to set up the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. If not for the coronavirus, people familiar with the calls say, they probably would have less to talk about now, but Obama has reached out a few times. He’s interested in her ideas for the pandemic response, and he’s impressed by how she’s selling them. He hasn’t made up his mind on the running-mate question, but a tweet at the beginning of April in which he praised Warren’s summary of the issues facing lawmakers was meant as a stamp of approval.

“He thinks that her economic message is a strong one, and that there’s real resonance right now,” one of the people talking with Obama recently told me.

Valerie Jarrett, who’s personally and professionally closer than anyone else to the former president, reminded me that she was one of the people who’d pushed Warren to run for the Senate initially, and that she’d always admired her, even though she knew that wasn’t a common feeling within the Obama West Wing. “She was fearless—and I respected that fearlessness. Did she break some eggs sometimes? Yeah, but you don’t usually hear that about men,” Jarrett said. “She’s done her homework; she clearly understands how to get her arms around a pandemic—as best one can.”

Jarrett has made up her mind on whom she wants Biden to choose. She wouldn’t tell me whether she’d landed on Warren, though she did say she had made her decision clear to Biden aides. Then, noting that I shouldn’t take this as an endorsement, she added: “She’s very competent. At a time like this, I think it’s important for the American people to see what competence looks like, to give them confidence that there are people who do care about science and evidence and are humane.”

Given how he got here, Biden has his own thoughts about what a running mate and a vice president should be like, and people who have spoken with him say he puts a premium on people who ran for president themselves.

But the political arguments against Warren stack up. First: She’s 70, which might make her a risky choice for a 77-year-old nominee who’d be the oldest president in history. If she were picked, I asked Warren, would she be ready to run if Biden declines to in 2024, when she’ll be 74? “We’re getting waaaaaay ahead of ourselves—and that way has about six A’s in it,” she said.

Then there’s her Senate seat: If Warren were elected vice president, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker would get to pick a temporary replacement, and he’s a Republican—though the Democratic majority in the legislature would likely force him to pick a Democrat. Still, there’d be a special election a few months later, and it was this very Senate seat that Democrats managed to lose in a 2011 special election. Democrats obsessing over the Senate have nightmares about the Massachusetts seat costing them the majority.

Those in the very small circle around Biden working on the running-mate question are doing their own trigonometry about how each of the options (including Senators Kamala Harris and Amy Klobuchar) would cost the campaign supporters—or win new ones. Warren’s fans, some Biden aides believe, are the most committed of Democrats, the kind of people who are presidents of their local Democratic clubs. Those people will vote for Biden no matter what, some figure. So would Warren attract a significant number of voters? Would they compensate for the voters she’d drive away, including some of the people otherwise willing to ditch Trump? Some of the voters considering Biden because he’s a moderate or because they see him as a safer choice than Trump would see Warren as a polarizing radical. And what about all the voters who would be disappointed that he didn’t pick a woman of color? Warren didn’t show strength with people of color during her own run. And what about the white working-class voters she never connected with, either in her presidential race or during her two Senate campaigns?

The lesson for many Democrats from 2016 is obvious: If you don’t give young people something to be excited about and you don’t give progressives a sense of being heard, your candidate will end up hiking in the woods while Donald Trump goes to sleep in the White House. Biden has consistently struggled to attract younger voters and much trust from progressives; with the exception of the few hours leading up to his Super Tuesday romp, he hasn’t generated much excitement.

With the coalition she built, Warren would seem to be able to help build enthusiasm—though, as a number of Democratic operatives pointed out to me, it hurts her case quite a bit that when the time came to vote, younger and progressive voters went overwhelmingly for Bernie Sanders.

A group of particularly noisy Sanders supporters have helped inculcate the idea that Warren is a traitor to the left wing of the Democratic Party. They’re frustrated that she ran at all, arguing that she divided the left. They blame her for a leak about a private conversation Sanders and Warren had in which, she claimed, he said that a woman couldn’t beat Trump. And they’re furious that she didn’t endorse him after she dropped out—or back in 2016.

“If she’d endorsed Bernie in 2020, she’d have more legitimacy,” a former Sanders-campaign official told me. If the goal is to bring the Sanders wing in, “she’s not a unifying figure.”

But Sanders isn’t going to be Biden’s running mate. Warren is the option who progressives, by a wide margin, say would make them more likely to vote for Biden, according to Sean McElwee, a liberal pollster with Data for Progress. She also tops the list for Democrats overall; in a May CBS poll, 36 percent of Democrats picked her, compared with 19 percent for Senator Kamala Harris, the second-most-popular choice. Polls of members of the Sanders-inspired groups Our Revolution and MoveOn show Warren as their top choice for Biden’s running mate, and it’s not even close: 62 percent of Our Revolution members picked Warren in an April email survey, followed by 22 percent for Stacey Abrams, 8 percent for Harris, 5 percent for Klobuchar, and 3 percent for Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer. Focus groups of younger voters conducted in recent weeks for NextGen America found that she was the name that came up most often as a running-mate choice.

McElwee thinks Warren is probably Biden’s best chance to connect with progressives.

“The sentiment among people who supported Bernie who really want to see his agenda implemented, they think Elizabeth Warren is the best way to make that happen,” he said. “For the people who supported Bernie for the sake of owning the wine moms, they’re probably not happy. But who gives a shit?”

Among those still disappointed and frustrated that Warren didn’t endorse Sanders is Sanders himself. Several people who have spoken with him told me he would have backed her if she’d been the one to emerge against Biden at the end of the primaries, and if she had backed him, he might be pushing for her in the conversations he’s had with Biden about building unity. But he’s not, at least so far.

Representative Ro Khanna of California, who was a national co-chair of Sanders’s campaign, is more enthusiastic about the prospect of a Warren vice presidency. “It’s a slam dunk for progressives that she should be vice president,” he told me. As for the reservations other Sanders supporters have, “There would be a lot of people who would come [based] on the policy. Warren’s policies overlap 90 percent.”

Warren tends to know what she wants to say, and tends to say it directly. But when I asked her what she’d tell people who claim that what happened with Sanders proves she’s not a true progressive, she paused to think about her answer. “I believe it was important that Bernie had the space he needed to make the decision about his campaign,” she said, choosing each word carefully. As for any questions about where she stands, “I want to see our government move in a more progressive direction because I believe that’s where America is and it’s what will help us build a better future.”

The current economic collapse is different from the last one—it was produced by an outside shock, not the system imploding on itself. But to Warren, that’s like saying a heart attack brought on by stress didn’t have anything to do with all the cheeseburgers and cigarettes. “For decades, resiliency has been squeezed out of our economic system, and that’s true at the individual family level and true at the global corporate level,” she told me. “When you squeeze out that resiliency, when the system tightens up, it produces short-term profits for investors and executives, but it means that when something goes wrong, it breaks hard. This recovery will take years—even with massive federal intervention. And without massive federal intervention, it will take even longer.”

Warren ran around Iowa and New Hampshire talking “big, structural change,” but when I asked her if she’s thinking about radical or revolutionary change now, she said the world looks a little different when half of all small businesses might be closing and tens of millions of people don’t know when they’ll be able to pay rent again. “I think of it as organic change,” she said. “It’s change that grows out of our circumstances.”

Warren is coming at the situation, as always, like a law professor, looking for a little crack in which she can build a whole new structure. Her Essential Workers Bill of Rights would establish basic workplace rules along with securing health care, whistleblower protections, and other rights. It started with another strategic call, to Khanna, whose progressive politics in a Silicon Valley district has made him a point person on ideas for tackling the enormous divide between the people who live in houses with olive groves next to their tennis courts and people who have been left out of the new economy entirely. “‘How is that these billion-dollar companies have been so mismanaged that they can’t make payroll?’” Khanna remembers her saying.

“If we can make this change for essential workers, then it opens the door to making change for all workers,” Warren told me. “Why should any worker be in an unsafe workplace? Why should any worker not have whistleblower protection? Why should any worker have to show up at work where they could get sick and not have paid sick leave and medical coverage? Think about how our world changes around that. And that all comes from where we are today—the fact that we’ve lost a brother, a grandma, a friend.” Her voice cracked on the word brother.

Ironically, what may be the biggest obstacle between Warren and a chance to change how the economy works is her history of doing just that. Several of the people who have Biden’s ear are former Obama aides who felt like Warren was pursuing her own agenda during her days setting up the CFPB, or during the days when she was using her Senate perch for moves like torpedoing a pick for an undersecretary of the Treasury because of his Wall Street background. Some key people around Biden are on edge about the thought of having to constantly be looking over at the vice president’s office, wondering what she’s working on.

Warren has spoken privately about feeling chastened by the 2020 primaries. “She put it all out there. She knows she lost. She knows Biden won,” someone close to Warren told me. “She knows we’re in a time of crisis, and her priority moving forward is helping make him successful.”

When I asked Warren about the ex-Obama aides’ misgivings, she gave me a long answer that started with: “I’m a team player. I want to get things done.” She ticked through her work setting up the CFPB as a success for Americans overall and for the Obama administration—and said that as a senator, she was doing her constitutional duty in a separate branch of government. “I know that can sometimes be a bumpy relationship,” she said. “That is my job.” She ended by repeating: “I am a team player because I want to get things done.”

Warren couldn’t go to her brother’s funeral after he died in April. She couldn’t do much beyond cry by herself, 1,600 miles away in Boston, holding the phone that she’d been calling Don on every day, twice a day, to check in. “To lose someone when you have to wonder what were their last days like? Were they afraid? Were they cold? Were they lonely? That is a kind of grief that is new to all of us. My brothers won’t get over this. They just won’t. None of us will.”

About 36 hours after Don died, Representative Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts told me, Warren was on a Zoom call with her, Khanna, and Representative Deb Haaland of New Mexico, strategizing about the Essential Workers Bill of Rights. Her brother didn’t come up directly, though Pressley, who’s also been working with her on racial-data collection, said he was clearly on her mind.

“She knows that her loss, that she deeply feels, is sad and tragic—but that there are millions of families that are grappling with that same loss,” Pressley said. “Even when she deeply feels something, she’s projecting that out.”

It’s a crass but real thought that has come up among some Democratic operatives in the past two weeks: Imagine Warren debating Mike Pence. The vice-presidential debate is currently scheduled for October 7, at which point it’s possible that 200,000 or more Americans will have died of COVID-19. She would be in the position to look at the vice president, who was put in charge of the coronavirus response, and talk to him about families like hers that will never be whole again.

Warren told me about a call she received from Biden the morning after her brother died. Their conversation was “one person who’d lost loved ones trying to console another person who just lost her beloved brother,” she said.

Connections formed in grief tend to stay with Biden. This one has certainly stayed with Warren.

After all their other phone calls, about everything from coronavirus testing to unemployment insurance, I asked Warren whether Biden now sees economic policy the way she does. Yes, she said, but that’s only part of it.

Then she took a practice swing at the kind of line that you will hear coming out of whomever Biden picks, but that now means something different, and personal, to her: “We need a president with empathy, a president who understands that people in our families are sick and dying, a president who cares about the loss of every single person in this country. That’s what Donald Trump can’t manage. And that’s what Joe Biden feels in his bones.”