A ‘White Rajah’ returns to Malaysia’s Sarawak, but this time to serve

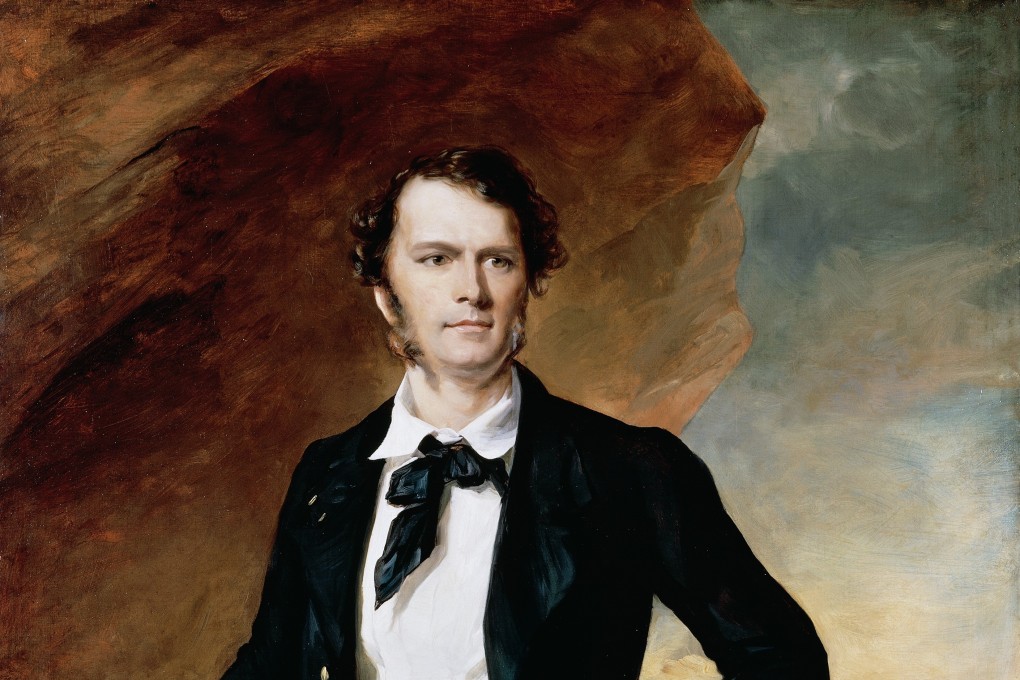

- The Brookes ruled Sarawak for a century until 1946, and are credited with building it into a modern state with its own government and constitution

- Jason Brooke, a sixth-generation descendant of James Brooke, the first Rajah, is looking to preserve the state’s heritage and his family’s identity

The Brookes are seen as having built Sarawak from a territory of disparate ethnic communities into a modern state, with its own government, constitution, flag and currency. Under their leadership, Sarawak expanded from Kuching, its capital today, to its current shape.

There’s nowhere else in the world with a story like this

With the support of the Sarawak state government, Jason Brooke, Anthony’s grandson, is looking to preserve the state’s heritage, with a focus on educating young people about its history.

His efforts began in 2010 with the archiving and digitisation of records and artefacts from the Brooke era. Then, in 2016, the Brooke Gallery museum opened in the restored Fort Margherita – originally built by the second Rajah, Charles Brooke – followed by another museum about his wife in the Old Courthouse in Kuching.