The Loft Meeting, Part One

Sam Jacobs is 24. He is tall and skinny, with brown hair, glasses, and a nose ring. Something inside him told him to give away his money, along with the power that money bestows, so he is sitting at the long, gray dining table in a loft on one of the loveliest streets in one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in Manhattan, opening a Google doc. The Google doc is because he is the secretary of the group, and everyone else in the loft can follow along as he types notes.

Hyatt, 32, who has curly hair tucked under a baseball cap, helps himself to a glass of water in the kitchen. Something inside him, too, told him to give away his money, along with the power that money bestows, and he will be following along with Sam’s notes during the meeting.

Jessie, whose gorgeous loft this is, takes her seat at the table and asks the group of five people, “Does everyone consent to the agenda?” She wears a Guns N’ Roses T-shirt and gold hoop earrings.

The ceiling is 18 feet high, and three enormous windows provide a pretty view of the street. The walls are painted white, the wood floors black. In a living area near the windows, a green tufted velvet sofa, an Eames chair, and an upholstered stool are arranged neatly on an oriental rug. An archipelago of potted plants fans out from one corner, and a collection of framed paintings leans neatly against the wall on the opposite side. It’s 87 degrees outside at five o’clock in the evening, but a soundless central air system keeps the place cool.

It’s a Sunday in July, and this is the weekly status meeting of the Action Committee of the New York chapter of Resource Generation, an organization founded on the belief that young wealthy people should give away most or all of their inherited money or excess wealth. Or, in the group’s words, “As part of a coordinated strategy to systematically redistribute wealth and repair the harm created by wealth extraction, RG asks our members to take bold action with the resources currently under our and our families’ control, moving toward greater alignment with humanity and the planet.”

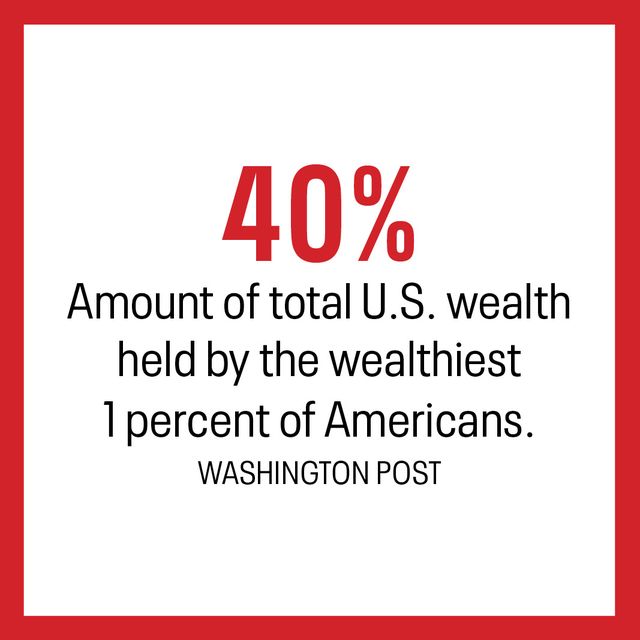

RG has 15 chapters across the country. It’s made up of wealthy individuals between 18 and 35 who are among the top 10 percent in wealth in the U.S., and its primary goal is to “redistribute all or almost all inherited wealth and/or excess wealth to social justice movements.” To help redistribute the power that goes with having money, RG recommends giving to organizations in which people in the target community (in other words, not just the donor), get to decide how it’s used.

In recent meetings the committee has been implementing something called sociocracy. “It’s dynamic governance that allows for everyone to be heard and to make decisions efficiently,” Jessie says, pointing to a worn copy of the manual Many Voices, One Song on the table. She calls the meeting to order. “Okay, first round. Sam, you start.”

“I’m Sam Jacobs,” he says. “My pronouns are he/him. I have been hustling on the Puerto Rico stuff. We’re all just so happy that Ricky [Governor Ricardo Rosselló] resigned. This was a queer and marginalized persons–led movement. But there is still a lot of work to do. Pass left.”

A person attending over FaceTime, late twenties, says they do not want their name or pronouns revealed in the media.

Resource Generation has been around since the mid-1990s, but it has expanded rapidly in recent years. “Basically, since President Trump was elected,” Jacobs tells me later. In the first six months of 2019 it broke an internal record when some of its more than 600 dues-paying members pledged $20 million to a variety of social justice and grassroots organizations.

RGers also participated in numerous protests this year in New York, Washington, Los Angeles, and San Francisco in support of immigration, abortion rights, racial and gender justice, the Green New Deal, Puerto Rican independence, and, most important, higher taxes on the rich. They hosted webinars with titles like “Class Privilege and Activism,” and in November Resource Generation will hold its annual conference, “Making Money Make Change,” in the Hudson Valley.

Next: “I’m Ila, she/her,” says a woman, 28, dressed in shorts, a T-shirt with “Santa Fe” printed on it, and a baseball cap with no logo. “I just got my puppy and it’s been pretty all-consuming.” She holds a squirming three-month-old dog on her lap and periodically reaches into a Ziploc bag full of dog treats on the table. “Pass left.”

Phone Call #1

T&C: You start all new memberships with the “money talk”—one on one, in which both people tell their money stories, their backgrounds. Why is this useful?

Iimay Ho [Resource Generation’s 33-year-old executive director. She grew up in Cary, North Carolina, attended UNC Chapel Hill, and worked at several social justice organizations before joining RG. She has assets of about $200,000, much less than many RG members—but, as she points out, it’s enough to put her in the top 10 percent for her age group]: If our whole society can’t talk about money and class, then how do we? So we do that by always talking about money and class.

I joined Resource Generation in 2013. I had been doing organizing work with, like, Asian-Americans and the LGBTQ community and doing aggressive fundraising work with them—but we never talked about our class backgrounds. I found it strange that I was part of the whole giving project, and we were raising money, but we never actually talked about our own relationship with money and class. I found out about Resource Generation and filled out the form on the website. The first thing they do is find someone in your area to sit down with you for the one-to-one conversation.

T&C: Did you feel flustered answering those questions at first?

IH: It was really not hard. I’m a person of color who identifies as queer, has other identities in which people might assume that I come from a poor, working class background. It was actually a relief for me to just finally be like, “No, actually, I had a lot that was passed down to me.”

T&C: So Resource Generation encourages honesty.

IH: Yes. There are so many myths and lies around the idea of meritocracy in this country. Even Trump’s whole, like, “I got a small loan.” I think we have this pervasive belief: If you work hard and you do the grind and you do the hustle, the American Dream is within reach for anyone. And what I’m trying to show from my stories is that so much of it is also due to systemic racism and who had access to what. Many of our members who are white have multigenerational wealth, because their parents or grandparents went to college on the GI Bill, or their ancestors had access to land ownership before any person of color was ever allowed access to land ownership.

T&C: I read the piece in the New York Times that mentioned Resource Generation, and some of the comments—

IH: I haven’t read the comment thread, so bless you for doing that.

T&C: A lot of it was like, “Oh, the poor rich people feel bad and they want to—”

IH: People have a love/hate relationship with rich people. Like when Mark Zuckerberg said he was going to donate, like, 90 percent of his Facebook stock—but to his own private LLC. We absolutely issued a public statement saying, “Hey, that’s not actually

philanthropy, that’s not cool. You’re still maintaining absolute control.” We got so much pushback, like, “Stop being so hard on Mark Zuckerberg.”

Coffee Shop Conversation #1

Scene: 61 Local, a Brooklyn coffee shop populated by work-from-home types wearing cool T-shirts and typing on new laptops. Late morning.

Sam Jacobs [beneficiary of a $25 million trust fund]: [via e-mail] I’m here, just up at the bar grabbing a bite. [He orders at the counter and then walks to a communal table in back and sits.]

T&C: I didn’t come with a list of prepared questions.

SJ: Cool. I’ll start with the basic outline of my money story. I grew up in San Diego. My grandfather started a company called Qualcomm with six other engineers. Qualcomm’s a cellphone chip—

T&C: I’ve heard of it.

SJ: After my grandfather retired, my dad became the CEO, and was for about 10 years. So, naturally, starting a Fortune 500 company gives you the opportunity to accumulate a shitload of wealth. My grandfather’s a billionaire. My dad, I think, might become a billionaire. At this point in my political development, it’s pretty clear to me that’s not something that is interesting to me. My first moment being responsible for a big pot of money was at 18, when my grandparents gave me and my siblings and cousins donor-advised funds with about $150,000 in them and said, “Go for it.”

[Last year he donated a portion of the growth of his trust fund income, around $750,000. He intends to do the same again next year and eventually to include some of the principal. In the meantime he works as a $115-an-hour SAT tutor for an agency.]

I really appreciated the trust that they put in us. I feel a really, really, really strong imperative to redistribute wealth. And I wish it wasn’t something that I had to do voluntarily. But given that it is, that’s no reason not to.

T&C: If you would, talk to me about the things that seem most radical to people you encounter and how you talk them through it.

SJ: One of the things we really harp on a lot is not just giving money away but also redistributing power. Philanthropy, broadly, lacks a real accountability mechanism, right?

T&C: The prurient part of this is: well, how much? Do you leave yourself destitute?

SJ: We have giving guidelines. [From the guidelines: “If you’re already giving more than 10 percent of your assets or income, set a goal to double your giving in the next one to three years—being willing to change our personal standard of living so that our collective standard of living improves.”] The way I think about it personally is, when you talk to a financial adviser, their orientation to thinking about capital is the more risk you take, the more reward you can get.

And to me that seems strange, because it doesn’t feel risky to put millions of dollars into a hedge fund when I know that I have other millions of dollars to back that up, right? That doesn’t feel, to me, risky in the same way that when someone in New York who is a delivery person gets on their e-bike, it might get hit by a car trying to deliver someone’s burrito.

T&C: It really is the most dangerous job that anybody can have.

SJ: It’s wild. I think we in RG think about risk on that level—something that feels like we have skin in the game.

T&C: Do you worry about passing on what you’ve inherited to, if you have kids, that generation? When I look at my two daughters, I’m like, “I want to be able to do all this stuff for them.”

SJ: That’s a really good question. If I’m doing this work in the right way, it will be clear to my kids and my partner, my family, that by moving this money into communities, it actually makes us more safe and more secure. I think of it as a trust fall into the movement.

T&C: In other articles about you guys, the comments have been—do you read any of them?

SJ: Yeah.

T&C: Super-vitriolic.

SJ: As they tend to be on the internet.

T&C: In particular, they were extremely critical of RG. “Oh, shut up” or “Poor little rich people.” I imagine that’s something that you expose yourself to—and you’re exposing yourself to now. Do you ever feel like, Oh, god, this is going to hurt?

SJ: [Hesitates a full 10 seconds, really for the first time in the conversation, before he speaks] Of course. Like everyone, my skin is not nearly as thick as I would like it to be or pretend that it is. And I think that, honestly, the kind of populist fervor against rich people is something that broadly I’m totally okay with.

T&C: Do you think there’s any chance there will be a revolution here in the United States? A violent one?

This is something I’ve thought about a lot. I think if there were an attempt to have a violent revolution, that shit would get put down so hard and so fast. I think people know that. I think part of that is the colonial structures that we have embedded in our minds. I don’t want anyone to get hurt. I don’t want anyone to die. But people are getting hurt and are dying now. I think the average life expectancy of working class people is declining, as it’s getting longer for wealthy people. That’s a redistribution of not just of wealth but of life—of literal life force from the lower classes to the upper class. So I guess I would call this current moment a violent revolution.

The Loft Meeting, Part Two

Sam hammers away at his laptop, and the other attendees read his notes as they appear on their phones or computer screens and occasionally murmur, “I like how you phrased that,” or, “I think you can leave that out.”

“I’m Hyatt, he/him,” says Hyatt. “I just got back from Detroit and CPB”—the Center for Popular Democracy’s People Convention, a gathering of more than 1,700 grassroots organizations. “We did some outreach to Movement for Black Lives and agreed to try to make some connections on actions. Our next meeting will be relationship building and power mapping. Pass left.”

Jessie: “Okay, it’s time for report-back. I’ll start. We had an outreach meeting for new members here this week. I counted 20 people including us, and everybody was really engaged and interested. We need to do followups in 24 to 48 hours.” Two members pass, and then Hyatt speaks about how, at protests at corporate headquarters, undocumented immigrants are often endangered: “I went to a workshop on how we, as people of privilege, can be helpful in actions. We talked about how we should be the people who go inside lobbies and undocumented people should stay safe outside.”

Jessie mentions that she celebrated her 25th birthday that weekend on Coney Island. “It was my first time there.” Then she looks at her watch. “Sam, upcoming events?”

“There’s an anti-ICE event, and a lot of great organizations will attend. We want to get 100 people who will take arrests. I’ll pitch it on Wednesday,” he says.

“Are there going to be partnerships coming out of this?” Ila asks.

Sam quickly makes a note on his laptop and says, “Good question.”

Coffee Shop Conversation #2

Scene: Muse, a brightly lit café in Park Slope, Brooklyn.

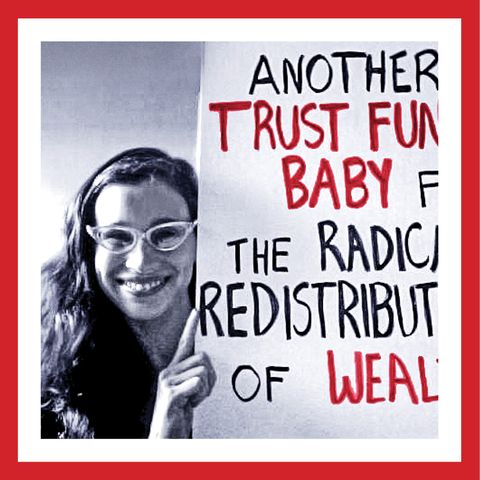

“Bananas rich girl gives away her money!” says Karen Pittelman, waving her hand. “The narrative is always about the person giving away the money—in this case me—and not the idea behind it.”

She is drinking iced mint tea and describing the way people react when they learn that she dissolved a $3 million trust fund set up by her grandfather when she was 25 and transferred the money to a private foundation that supported grassroots organizing. “The point is to turn over the power that comes with the money, too.”

“My family were worried,” she says. She is wearing cat’s-eye glasses, a black peasant blouse, and a neatly pressed flower-print skirt. “They made the condition for dissolving the fund that I set up a foundation, but I handed over power to redistribute the funds over the course of nine years, to an activist women’s board.”

One of Resource Generation’s missions is to get rich people to examine the visible and invisible ways they have benefited from their wealth. “My whole life I was taught, ‘You are the future leaders of America. You should always be in charge. You know best,’” Pittelman says, referring to her experience at Horace Mann, one of New York’s top private schools. “I’ve got news for you and everybody else: I grew up around those people, and plenty of them were not smart. But everybody I came up with is at least a doctor, lawyer, hedge fund manager, or corporate executive—and that has everything to do with how class privilege works and almost nothing to do with merit.”

Pittelman joined RG in 1998, around the time she dissolved her trust fund. “I had already decided to give away my money, but it was a relief to find other people in similar situations.” Back then the group, called Comfort Zone, mainly encouraged young people with wealth to donate their money (the name change came in 2000). Pittelman became RG’s program coordinator and focused on expanding ways the members could use their privilege—social access as well as money—to fight for social justice causes.

Now 44, she has aged out of RG, so she advises young people with wealth on how to use their money to support causes they believe in. Often this includes negotiating with families. “You’re not necessarily going to convince your died-in-the-wool Republican grandma that… Well, anything, probably. But you probably can move the needle a little bit.”

Coffee Shop Conversation #3: A Concerned Parent

Scene: Le Pain Quotidien at East 64th Street and Lexington Avenue in Manhattan. We enter midconversation.

Melissa Fetter [serves on the board of NPR and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston; chair of the Stanford University Arts Advisory Council; wife of the former president and CEO of Tenet Healthcare]: It’s my understanding that one thing Resource Generation is very focused on is empowering people in the underserved communities to create the change. I think that’s an important distinction. [She sets her latte down.]

T&C: Yes, one of the fundamental things is the notion of giving away power.

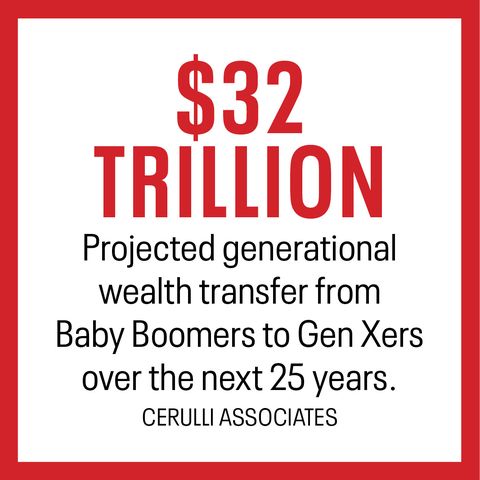

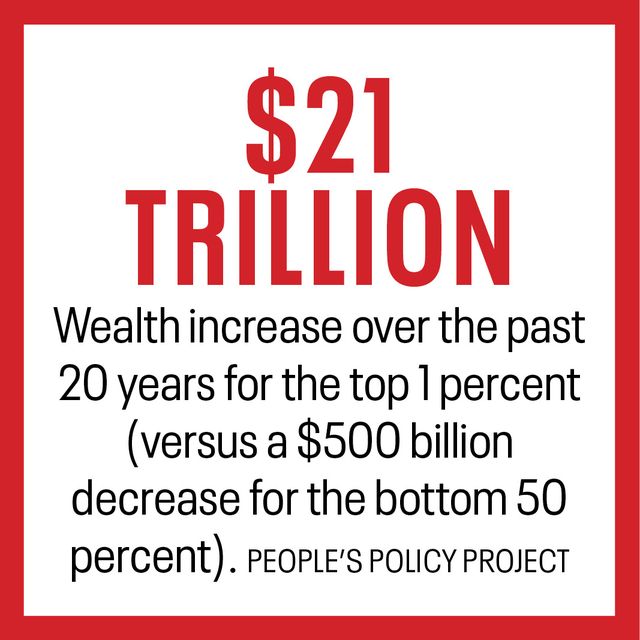

MF: They seem dialed into this idea that, I’m not sure—is it relinquishing power? Or is it acknowledging, “I have the influence to change things, and I’m going to bring others in on this to work with me.” Empowerment versus saying, “I’m going to give all my power to you.” I mean, I think it’s in the trillions, the transfer of wealth from my generation to the next generation that’s going to occur in the next 20 years. It’s notable that this group of young people with influence and resources—they want to do everything they can to try and use that to fix what needs to be fixed in this country. I admire what they’re doing.

Maybe I should wait for your questions. But kind of top-of-mind is that when young people have grown up without ever having wanted anything, it’s very easy, I think, to be overly optimistic and not realize how much it takes to achieve the baseline things of being able to have a comfortable home and put your kids in a good school, and give them experiences that you had as a child.

T&C: Yes.

MF: Right? And so part of me—and I think my husband will share this view—thinks, Don’t be so quick to give away what you have right now, because, yes, eventually you’re going to inherit more when we pass. But you just never know what’s going to come up in life.

T&C: I’ve got a nine-year-old and a seven-year-old. I’m looking into the barrel of a gun: How am I going to get these kids through college?

MF: Exactly.

T&C: A lot of the Resource Generation members I’ve spoken to have talked about fixing the system.

MF: My children and their friends—I can’t make a general comment about all people ages 20, 24, and 28—seem to be so much more genuinely concerned about the world around them and being content in their work, and less concerned about just acquisition of assets and making money. I find it heartening. We’ve handed this generation kind of a messed-up country, and I can see how they wake up and say, “Wait a minute, something really big has to change here.”

T&C: Has your daughter’s involvement made you and your husband rethink the notion of passing on money to her and her siblings?

MF: I don’t think so. I think that whether she was interested in this field or not, we would still be somewhat cautious about giving too much too soon.

Phone Call #2: Her Daughter

T&C: Can you hear me okay?

Holly Fetter [28, a student at Harvard Business School, from an unspecified airport]: Yep.

T&C: I had a really nice time with your mom.

HF: Yeah, she said she had a really nice time with you.

T&C: Could tell me how you heard about Resource Generation, and why you joined?

HF: [sounding apologetic] Yeah, yeah. Just also, quickly, I’m boarding this flight in around 20 minutes.

T&C: [sounding accommodating] Okay.

HF: So, let’s see. I kind of grew up knowing that I was wealthy, but I didn’t totally understand it. And then when I was in college, Occupy Wall Street started happening. I went to a rally one day in San Francisco where a bunch of activists had constructed a giant caricature of a CEO. It was, like, pinstripe suit, pot belly, mustache—like the Monopoly man. And everyone in the crowd was invited to pull down the CEO cardboard cutout. I’m not sure if my mom mentioned this, but my dad was the CEO of a Fortune 500 company. So it was this crazy moment where I was like, “Oh shit.” I went home and frantically Googled “rich kids social justice.”

T&C: Did you talk about it with your parents?

HF: It’s funny, because I’m gay, so I had to come out to my parents as gay, but I think coming out to my parents as left-wing was actually harder. I think sometimes my parents perceive my politics as a rejection of them and who they are, and I really strive to help them understand that I wouldn’t be involved with Resource Generation if I didn’t care deeply about them and care deeply about honoring my relationship with them and the truth of my family story.

I fundamentally believe my family, and families like mine, will be a lot happier when we don’t have this sort of burden and… Sorry, burden is the wrong word, but the… I guess I’ll say it: the burden of feeling responsible for a lot of the pretty serious injustices and inequities that we see manifested. And I don’t mean to say that as, like, “Oh, it’s so hard to be wealthy.”

T&C: Like, we need to be able to talk about money.

HF: I think that’s a big part of it: trying to shift the conversation around wealth in this country. [Pauses] So, I’ve got to board this flight. But please feel free to call me. I’m around this weekend.

The Loft Meeting, Part Three

The rest of the meeting, Jessie explains as the evening wears on, will be dedicated to hashing out some questions about process. Process is very important to Resource Generation. Look at their website, resourcegeneration.org (if you haven’t already by this point in the story). It’s full of advice, resources, and facts. The “RG’s Giving Guidelines” section offers statistics meant to help users determine where they fall on the economic spectrum. A giving pledge has five levels, from “Start the Journey” to “Return the Wealth.”

You could spend hours in the Resource Library, which offers everything from a financial adviser database to definitions of the group’s main advocacy goals to articles and studies on how wealth is divided by racial and generational lines in the United States. The site has bios of RG’s 15 full-time staffers and its 13-person National Members Council, and the affiliations of its 11-member National Board of Directors, all of whom are on the staff or boards of other national nonprofit action groups and giving funds.

And while it’s easy to smirk at a bunch of privileged youths meeting in a fancy loft, being really serious about who says what, when, and how, here’s the thing: The July 2019 meeting of the Action Committee of the New York Chapter of Resource Generation is the most productive meeting I’ve ever attended. They accomplish things. They navigate interpersonal issues. They set goals. They’re a lot more organized, not to mention civic-minded, than I was when I was in my twenties.

“Let’s start with a picture-forming round,” Jessie says, and the members take turns asking questions: “How do we decide what things need to be their own circle?”

“What’s the difference between a project circle and child circle?”

“Who takes lead on project circles?”

At 10-minute intervals Jessie moves the meeting to a new stage: proposal-forming round, synthesis round, clarifying round, feedback round, consent round, and closing round.

Toward the end, the person who does not want to be named says, “This process is interesting, but I can’t say I love it. It doesn’t feel like a conversation. It could be a little more fun.”

“I agree,” Sam says. “This felt long and arduous. We need to spend more time with book. Hyatt, I feel like I snapped at you. I’m sorry about that.”

“I realize this part is boring,” says Hyatt. “But I’d like to offer that, as people of privilege, I feel like this work is the most important thing we’re doing.”

Everyone nods in agreement. As efficiently and swiftly as it was conducted, the meeting concludes, and the Action Committee files out onto the street, past the flowerboxes and taxis and bikes, each returning to his/her own corner of the city.