The Servant Economy

Ten years after Uber inaugurated a new era for Silicon Valley, we checked back in on 105 on-demand businesses.

In March 2009, Uber was born. Over the next few years, the company became not just a disruptive, controversial transportation company, but a model for dozens of venture-funded companies. Its name became a shorthand for this new kind of business: Uber for laundry; Uber for groceries; Uber for dog walking; Uber for (checks notes) cookies. Larger transformations swirled around—the gig economy, the on-demand economy—but the trend was most easily summed up by the way so many starry-eyed founders pitched their company: Uber for X.

This micro-generation of Silicon Valley start-ups did two basic things: It put together a labor pool to deliver food or clean toilets or assemble IKEA bookshelves, and it found people who needed those things done. Academics called this a “two-sided market,” but to a user, it meant tapping on a phone and watching the world rearrange itself to satisfy your desires. Convenience drove consumer demand. Economic need and work flexibility drove the labor supply. At least in theory.

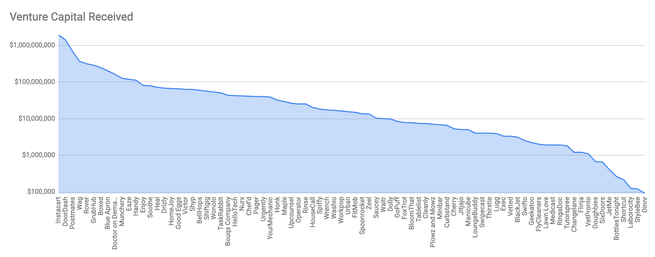

Now, a decade since Uber blazed the trail, and half that since the craze faded, we built a spreadsheet of 105 Uber-for-X companies founded in the United States, representing $7.4 billion in venture-capital investment. We culled from lists, dug in Crunchbase, and pulled from old news coverage. It’s not a comprehensive list, but it is a large sample of the hopes and dreams of the entrepreneurs of the time.

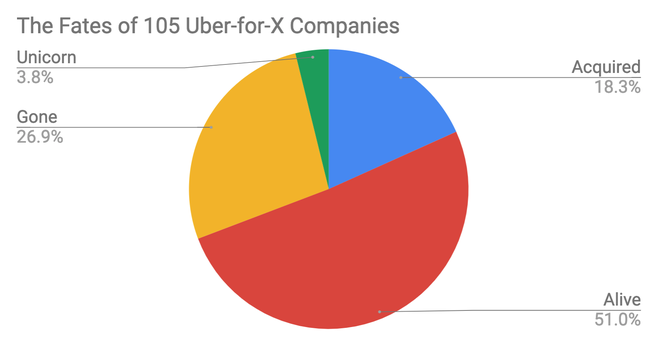

Of this group, four—DoorDash, Grubhub, Instacart, and Postmates—are unicorns, start-ups valued at more than $1 billion. (Notably, all are in the delivery business.) Forty-seven are gone—28 simply closed down; 19 were acquired. But 53 are neither unicorn nor roadkill. They remain alive in the great morass of the economy, successful but lacking explosive growth; or stumbling along with scaled-back ambitions; or barely functioning, like zombie start-ups. There are your weed start-ups such as Eaze, your high-end-grocery delivery such as Good Eggs, and some less high-profile companies that have found their footing as regular businesses such as Plowz & Mowz, a company in upstate New York that’s Uber for plowing and mowing. Blue Apron went public to much fanfare, but it has seen its share price fall under $1 as its results disappoint public investors. Other companies—such as the dog walkers Wag and Rover—are still on the rise, and knocking on the $1 billion private valuation. And then there are the more under-the-radar players, such as Waitr, which recently went public and, though its shares have been volatile, has a public valuation of more than $600 million.

The unicorns have taken huge sums of money: on average, $1 billion in venture funding each. For comparison, before going public, Google—in total—raised $36.1 million. But it takes more money to open up offices in cities across the country than it does to scale up a software platform by spinning up more clusters at a data center. So the Uber-for-X companies followed much more closely in the footsteps of Uber, which has raised more than $24 billion in private markets.

As a group, all of these companies have brought hundreds of thousands of people into new work arrangements that are more than a gig but less than a job. They’ve rearranged the way people get basic tasks done, and they’ve wired those in local industries—handymen, house cleaners, dog walkers, dry cleaners—into the tech- and capital-rich global economy. These people are now submitting to a new middleman, who they know controls the customer relationship and will eventually have to take a big cut, as Uber drivers would be happy to tell them. And because the ideas themselves are not rocket science, the competition has been fierce. Just in this sample, there are eight Ubers for doctors, six booze-delivery companies, five laundry services, and four each of massage, dog-walking, and car-washing start-ups. To drive faster growth, they have to charge customers less (increasing demand) and pay workers more (increasing supply), then fill the gap with venture-capital funding.

That’s one reason why most of these companies—even the huge ones that have taken hundreds of millions of dollars—are not making money, but losing it nearly as quickly as Uber itself. The basic economics of moving human beings and stuff around the physical world at the touch of a button is not an obviously profitable enterprise. And even when venture capitalists are willing to buy growth for these companies, they still tend to pay their workers close to minimum wage—especially after considering expenses—and generally don’t provide the nominal security of an actual job.

Looking at this incredible flurry of funding and activity, it’s worth asking: These companies have done so much—upended labor markets, changed industries, rewritten the definition of a job—and for what, exactly?

Now you can do stuff that you could already do before, but you can do it with your phone. What it takes to make that work is incredible—venture capitalists have poured $672 million combined into Wag and Rover!—but the consumer impact is small. Instead of taking a number off a bulletin board in a coffee shop and calling Eric to walk Rufus, you hit a few buttons on your phone and Eric comes over. Very successful companies, the Ubers and Lyfts, do begin to shift urban systems—but only once they’ve been operating for long enough. Even figuring out whether ride hailing is taking cars off or adding them to the road is complicated.

It’s not hard to look around the world and see all those zeroes of capital going into dog-walking companies and wonder: Is this really the best and highest use of the Silicon Valley innovation ecosystem? In the 10 years since Uber launched, phones haven’t changed all that much. The world’s most dominant social network became Facebook in 2009, and in 2019, it is still Facebook. Google is still Google, even if it is called Alphabet.

Politically, the world is night and day, though. In that context, these apps take on a strange pall. The haves and the have-nots might be given new names: the demanding and the on-demand. These apps concretize the wild differences that the global economy currently assigns to the value of different kinds of labor. Some people’s time and effort are worth hundreds of times less than other people’s. The widening gap between the new American aristocracy and everyone else is what drives both the supply and demand of Uber-for-X companies.

The inequalities of capitalist economies are not exactly news. As my colleague Esther Bloom pointed out, “For centuries, a woman’s social status was clear-cut: either she had a maid or she was one.” Domestic servants—to walk the dog, do the laundry, clean the house, get groceries—were a fixture of life in America well into the 20th century. In the short-lived narrowing of economic fortunes wrapped around the Second World War that created what Americans think of as “the middle class,” servants became far less common, even as dual-income families became more the norm and the hours Americans worked lengthened.

What the combined efforts of the Uber-for-X companies created is a new form of servant, one distributed through complex markets to thousands of different people. It was Uber, after all, that launched with the idea of becoming “everyone’s private driver,” a chauffeur for all.

An unkind summary, then, of the past half decade of the consumer internet: Venture capitalists have subsidized the creation of platforms for low-paying work that deliver on-demand servant services to rich people, while subjecting all parties to increased surveillance.

These platforms may unlock new potentials within our cities and lives. They’ve definitely generated huge fortunes for a very small number of people. But mostly, they’ve served to make our lives marginally more convenient than they were before. Like so many other parts of the world tech has built, the societal trade-off, when fully calculated, seems as likely to fall in the red as in the black.