The Dark Story Of Diamond Distributors: The Company That Controls Your Comics

How Did Diamond Corner The Market?

Photo: MarvelDiamond didn’t corner the market through its love of the industry, or by selling products they felt best represented their company; they did it with cold, hard cash. After establishing themselves in the early '80s, Diamond hired an accounting firm and a “no nonsense” CPA to keep the company on track. The CPA, Chuck Parker, didn't care about comics. He could have been working for a construction cone distribution company, and his business strategy would have been functionally the same.

His one and only goal was to make the company as much money as possible. There’s nothing inherently wrong with wanting to make a lot of money, but when commerce and art mix, someone is bound to get hurt. It's never the numbers guy. Parker, and others at Diamond, used huge amounts of capital to ensure that they had the biggest, best infrastructure of any comic book distributor.

During Diamond’s rise to power, other (somewhat) business savvy comic book fans were inspired, and felt they could do a better job at distributing comics to stores because of their love of the art. That turned out to not be the case. Many of the upstart distributors were out of their depth, and quickly folded. If the failing distributors had any significant backstock, space, or anything worth buying, Diamond bought them up at what one can assume was a very "reasonable" rate.

Distributors that didn’t fold due to their business inadequacy were crippled by Marvel and DC offering Diamond better trade terms, which more than likely included price breaks and incentives due to their efficiency and the size of their operation. Smaller distributors, who weren’t given the same breaks as Diamond, couldn’t compete and either shut down or were bought up, making Diamond the only business in town.

Diamond Makes It Impossible For Small Creators To Get Into Stores

Photo: Top Shelf Productions / BlanketsIf you’ve managed to rise through the comic book hierarchy and have your work picked up by any company with name recognition (Marvel, DC, Dark Horse, Image), then you don’t have to worry whether or not Diamond will distribute your work. Or, at the very least, you don’t have to worry about dealing with them on a face-to-face basis, because someone else can do that for you. But if you’re an independent publisher, or you’re just trying to get your small print comic into stores, then you’re in for an uphill battle.

In 2009, Diamond increased its order minimums from $1,500 to $2,500, meaning that a book has to make at least $2,500 in revenue to even be listed in Diamond’s preview catalogue. If you’re a first time publisher, or if your book is so small the possibility of making that much money short term isn’t realistic, then you’re out of luck with comic shops. The only other route is to personally visit shops with your book, and convincing them to take a chance on selling it.

When the change to their order minimums was announced, a spokesperson for Diamond stated, “That does not mean that Diamond is going to cancel or not carry books which appear in the Previews but do not reach the benchmark. But it does mean that if you have a line of books which consistently do not meet that mark, you will not be getting your books listed in the Previews for long.”

If your book doesn’t sell the required $2,500 from the jump, then your following effort either won’t get distribution, or you’re going to have to jump through promotional (and kind of degrading) hoops to get your next book on the shelves.

They Are An Actual Monopoly

Photo: United Plankton/Bongo Comics / AmazonSmall artists who have to deal with Diamond have obviously had negative experiences with the company, but they've got to be the only folks who complain about the distributor, right? No way. On the opposite end of the spectrum from DIY artists are the stores who buy their product from Diamond. Because the distributor is the only company they can buy from, there’s no one else they can give their business to when an order is wrong or something is damaged. They just have to live with it, because there’s no other option.

By the mid-90s, Diamond gained such a stranglehold on the comic book industry, the Federal government couldn’t deny something seemed fishy about their business practices. Specifically, that whole thing about Diamond buying up all of their competitors until they were the only game in town ("town" here means "the entire United States"). In 1997, the U.S. Justice Department launched an antitrust investigation into the alleged monopoly of Diamond. After a three year investigation, they decided no further action needed to be taken.

See, while the company did indeed hold a monopoly on singles comic books in North America, they didn’t hold a monopoly on book distribution. Diamond founder and CEO Steve Geppi later noted how the company worked closely with the DOJ to delve into the comic book industry. He said, “We were confident that we had conducted our business in a fair and ethical manner and that the DOJ would concur. Now, over three years later, they have finished an exhaustive look at not just Diamond, but the entire comic book industry, and have agreed with us that there is no cause for action. Obviously, we felt that was the case all along, and we're pleased with the Department's decision."

Even though the DOJ decided to drop their investigation into the company, they still made it common knowledge that Diamond does in fact have a monopoly on the industry. If they don’t want to work with a specific bookstore, then they can do anything in their power to make the lives of the employees of said shop a living hell. In 2015, Mimi Cruz, the manager of Night Flight Comics in Salt Lake City, detailed how the monopoly was still wrecking sales for both publishers and booksellers by either mishandling orders, or simply not fulfilling requests they agreed upon.

In a lengthy blog post, she wrote, “We all suffer the negative results of that monopoly with increasingly poor service. It is harmful to the commerce of our industry as a whole.” If only there was a second, or (dare to dream) a third distribution company.

Diamond Can Essentially Cancel Titles It Doesn't Like

Photo: Eclipse ComicsWhen you’re the only game in town, you get to make the rules. And if the person in charge is a prude (or worried about being able to sell as many comics to as wide an audience as possible), then you’re going to have to deal with a good amount of rules.

From the 1960s to the '80s, the Comic Code Authority worked in a similar way to the MPAA. They gave notes on the content of a comic book, decide what could and couldn’t be printed, and set a series of changing rules for the entire comic book industry. Throughout the decades, the amount of sex and violence allowed in comic books changed, and by the '80s you had artists like Frank Miller straight-up murdering characters in his books, rendering the code useless. This didn’t sit well with Diamond.

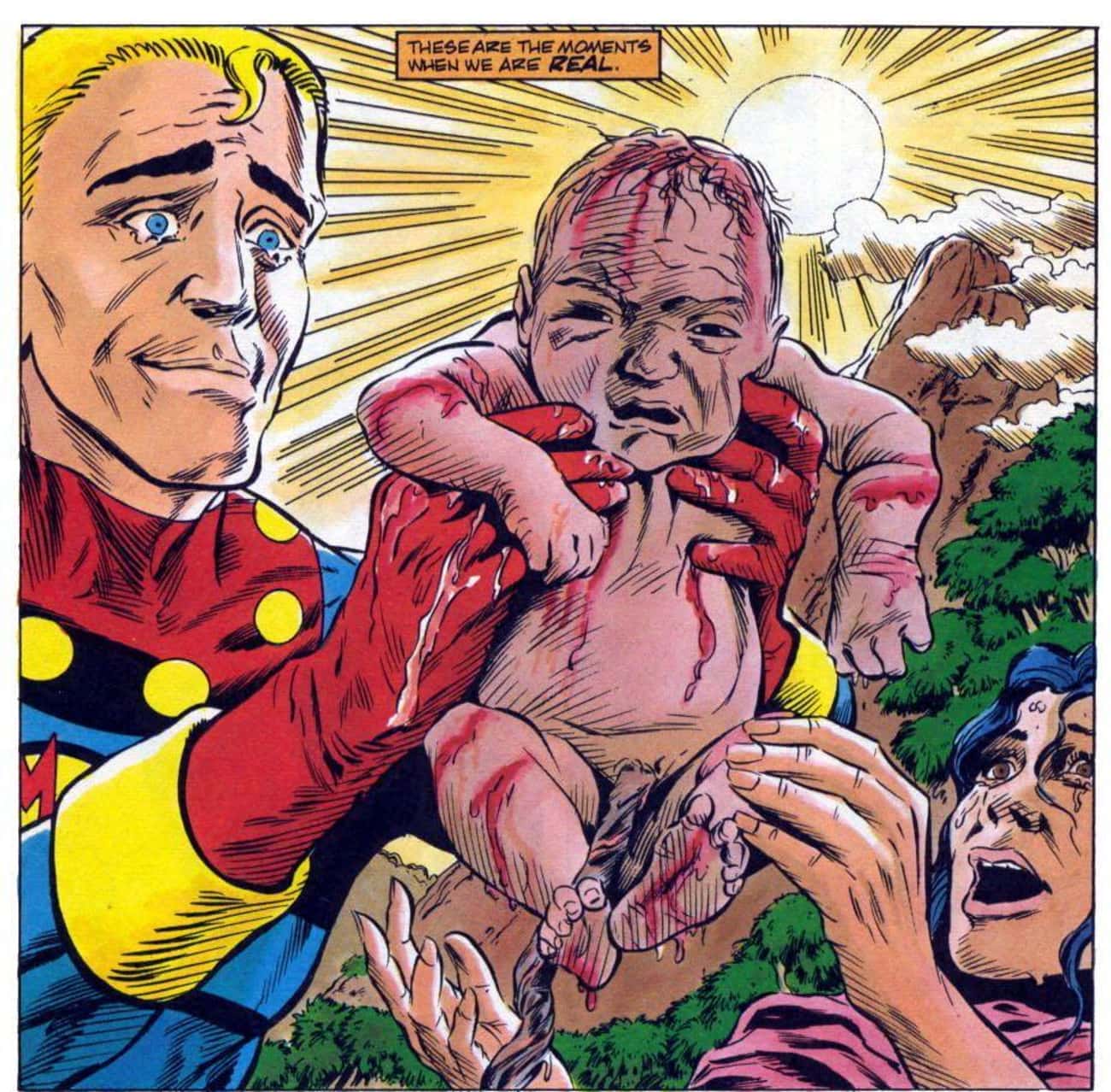

In 1986, Miracleman #9 depicted the graphic birth of a child. The book’s publisher, Eclipse, received some negative mail on the subject. The negative press wouldn’t have been a big deal, but the issue was exacerbated by Steve Geppi, CEO of Diamond Comics, who told his retail clients they needed to complain to publishers about their lack of censorship, specifically in the case of Miracleman.

Geppi then went on a crusade against Miracleman. He even brought it up during a television interview, freaking out Marvel and DC and forcing them to create their own codes of conduct. It almost ended the run of Miracleman, and destroyed a healthy source of income for Eclipse comics.

Why was this kind of activity tolerated? Admittedly, a distributor can be a powerful ally or foe, but they don’t make the product. In fact, they need to product to survive. If Marvel and DC would have just told Geppi to relax (or worked together to figure out an alternate means of distribution), then the idea of a middle man being able to say which comics can exist and which cannot wouldn’t be such a frightening and realistic possibility.

They Make It Impossible To Get An Accurate Read On Their Sales

Photo: MarvelFor some reason, it’s almost impossible to get an accurate count of worldwide comic book sales. You wouldn’t think this would be an issue, since there is essentially one distribution house that calculates orders, files them, and then sends out the product. However, funny book sales numbers are as mysterious as Wolverine’s backstory.

Out of motivations either as Machiavellian as a desire to control which books sell by creating the illusion of higher sales, or as simple as not wanting to let their internal numbers out into the world, Diamond only recently started giving out sales details. They still don’t put out hard numbers, but rather a top 300 list of titles based on the amount of books ordered, instead of the actual number of copies sold in stores.

It would be a little extra work to reach out to clients and find out what sold in which markets each month, but wouldn’t you think that’s exactly what a giant company like Diamond would want to do? Not only would it help them keep track of what’s actually selling, but their clients would probably love getting a little one-on-one time with their distributor.

To make things even more confusing, there’s the question of digital comic sales, which Diamond doesn’t even seem to keep track of. If they do, they aren’t sharing their numbers. Digital sales account for a fraction of tactile sales, but it's another situation where Diamond could turn itself from villain to hero by simply providing some numbers to the people who need them. They could help customers, booksellers, and publishers make more informed decisions about what they respectively purchase and create.

The numbers game Diamond plays isn’t out of the ordinary for the distributor, but it’s still disappointing to know they think they can do whatever they want. That extends to hiding numbers which should be pubic knowledge. Now more than ever, it's important to have transparency in the comic book industry.