Cooking As A Service

This tweet made me think a lot:

First of all, as much as I hate this idea, I think this notion is correct. This trend has been happening for a long time, and it’s going to keep happening. I think it’s a great illustration of what really happens in “access” or “as-a-service” economies: as friction goes away, we turn away from owning assets and towards consuming services as a way of fulfilling our jobs to be done. There are good parts to this, and there are bad parts; let’s talk about some of them.

The trend of increasingly outsourcing food production is new but not that new for North America. (In other parts of the world like India, where the economy and labour market is arranged differently, you’ll have a very different story.) If we take a look at the data, we can see the meaningful long-term shifts in cooking practices that have taken place over the past two generations, up until today’s mobile era where the internet has started to reshape things again.

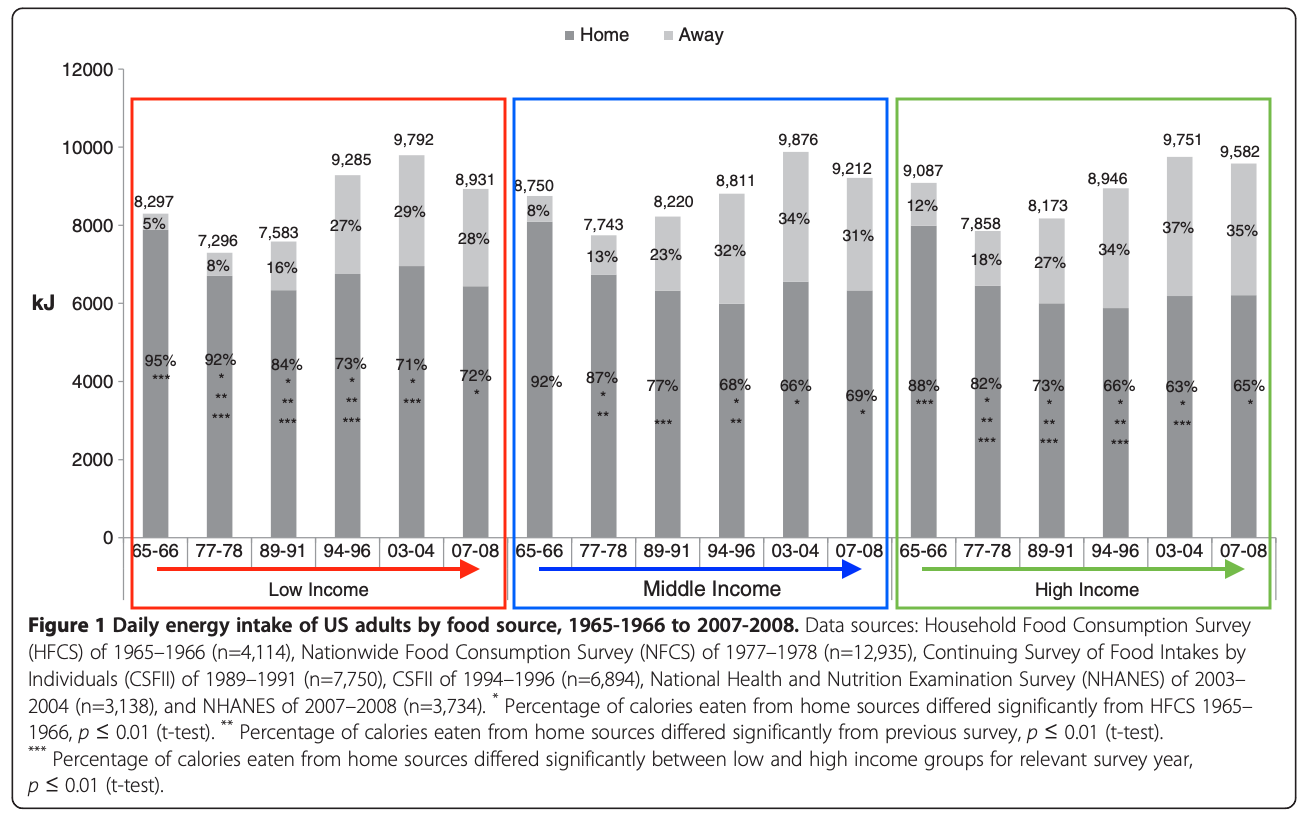

This paper goes extensively through fifty years worth of data on the relative prevalence of food prepared inside the home versus food prepared outside the home: Cooking As A Service. The original graph is a little tricky to look at, so I added the coloured boxes and time arrows to make it easier to read. It’s first split into three sections: low, middle and high income, and then within each income group, the bars represent time periods: representative years from the 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s, early 2000s and late 2000s.

A few overall trends are pretty clear from this graph. First of all, there’s a clear long term trend: outsourced Cooking As A Service has progressed from rare (<10%) to routine (28-35%) over two generations. This transition took place over several decades, although if you had to pick one inflection point it’d probably the early 90s.

Second, the overall trend is not dominated by any one income group. While it’s certainly true that high income earners may be dining out differently than low-income earners, the long run trend is that low, middle and high income earners are all choosing to outsource food preparation at more or less the same rate.

So what are the most important forces behind this? There’s a few worth emphasizing:

- First of all, overall living standards have gone up since our grandparents’ generation. More people, for more of their meals, are opting to pay other people to do the work of cooking for them as a service. The flip side of this is that more people are employed in Cooking As A Service businesses each and every year, which makes sense.

- Second, ever year our incremental improvements in technology, management, supply chain efficiency, and so forth are turning food prep into an activity that can be increasingly done on top of a “back end cloud”. All of the line item costs in commercial food preparation, including labour, have become highly reliable, interchangeable, inexpensive component parts. Businesses like McDonalds at the cheap end, or say Olive Garden or Sweetgreen as we ascend the price ladder, are able to mass-produce hot cooked meals that are affordable, tasty and consistent (although not necessarily healthy). The same goes for the infinite varieties of international cooking that we’ve learned how to refactor on top of the North American food service ecosystem.

- As Cooking As A Service expanded from <10% to 25-30+% of our eating, we grew to consume and expect a far greater selection and variety of food compared to when we did all our cooking ourselves. Our consumption choices around what food we eat gradually pivoted from “What am I able to cook for myself” to “Is this exactly what I want to eat, yes or no?” Once you transition into “is this exactly what I want, yes or no” territory, it’s very hard to go back; it becomes a part of the standard of living that we expect.

I wrote a while back about this general phenomenon: as friction goes away, we turn from asset ownership to service consumption as our preferred model for fulfilling jobs-to-be-done. The forward-looking example I usually use here would be turning from owning, driving and maintaining your own car (asset ownership) to increasingly relying on Ubers, micro-mobility, or other kinds of “functional” transportation (transportation as a service).

Cooking, we can see here quite clearly, is following the same trend except on a longer time scale and for a more convincing slice of the population. (This is a good reminder that Access Economy style service businesses don’t mean “sharing”, as in “we all share the same coffee machine that is somehow passed back and forth frictionlessly between us”. It means “We pay someone at Starbucks to make the latte for us.” The access economy isn’t about sharing, it’s about getting.)

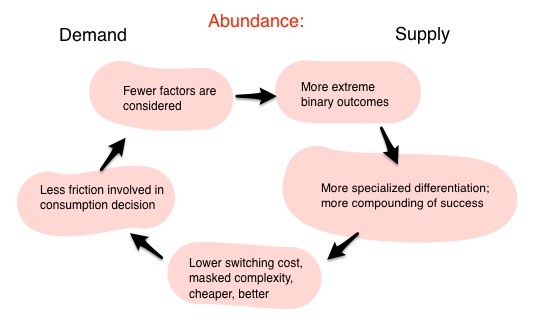

There are all kinds of forces behind this overall trend, but in general the supply side and the demand side are reinforcing each other in a positive feedback cycle. We move progressively from an environment where we consider many factors when making a decision to one where we make only one: is this exactly what I want, yes or no? In cooking terms, this meanings a gradual transition away from one where we have ownership over our own cooking assets and cooking capacity and then weigh many factors when determining what to cook for ourselves, and towards one where we simply consume whatever is available on-demand, with every aspect of cooking outsourced away.

Furthermore, I would not be at all surprised if these eating patterns ultimately formed a bifurcated distribution for any given individual: many different differentiated options on one side (specific restaurants that cook a particular exotic food, like sushi or Thai food, that we decide to eat impulsively) and a basic but good Default option on the other (the prepared food section at Whole Foods, or the equivalent). When we shift to “yes or no” decision-making in worlds of abundant availability, our consumption patterns adjust accordingly. Food is no different than media or retail.

For Patrick’s prediction to come true, though, we’ll have to break through another meaningful adoption threshold for the mass market. We’ve already broken through one over the past fifty years (from <10% to 25-30%) but we’ve plateaued there for the past decade or two. It’ll take another technological and cultural wave of change to break us through to the next level: from frequent (30%) to default (>50% of all meals across the board). What are the contenders for what will drive this change?

On the supply side, I think it’s pretty clear to everyone watching that food delivery companies like Uber Eats and Doordash just a preview of the disruption that’s really to come for the Cooking As A Service industry back-end. The real company to watch here is Cloud Kitchens, Travis Kalanick’s new gig (which, people may not know, was originally a project started and backed by Social Capital and friends before Travis came in and bought out the whole thing.) On the demand side, I think the most unrecognized but powerful element of what the internet and frictionless distribution is the increasingly ubiquity of “is this exactly what I want, yes/no” as a consumption trigger. Specialized prep on top of utility back-end food infrastructure reinforces itself.

From a couple of anecdotal conversations I’ve had with restaurant managers about this, it seems like once you open yourselves up as a restaurant that can be found on the delivery apps, a huge percentage of your kitchen volume switches over to fulfilling those orders, and your front-of-house costs get hung out to dry as increasingly unnecessary. Flexible, modular kitchens that are available for rent for any chef who wants to cook in it, and that have easy access to delivery cars and which pay for no front-of-house extras seem pretty obviously like the next iteration of back-end Cooking as a Service, and I wouldn’t be at all surprised to see them pop up everywhere soon enough. If they can collectively bring down the cost of outsourced cooking another 20-30%, I think the economics start looking pretty compelling for outsourced cooking (including delivery) to effectively pay for itself out of the savings incurred by paying for ingredients and cooking equipment in bulk. At that point, kitchens start to truly become optional.

Finally, it’s worth asking: is this good?

What’s certainly good about this long-term trend is that it’s a way of giving people back time. Food prep is something that’s far easier to do in large batches than in small batches, and eating is someone that everybody has to do, multiple times a day. So reorganizing the way that we all eat in a way that batches food preparation more efficiently ought to be a net win: everybody gets more time back. Having the time, equipment and setting to cook a nice meal for one’s own is certainly a nice thing to have; in time this may become effectively a luxury good (albeit one where a large majority of people will still have kitchens for the foreseeable future, even if they never cook in them).

One thing that’s bad about this trend, though, is that when you outsource food preparation (and everything that goes into it) into Cooking As A Service, then you turn all aspects of food into something that’s being sold to you. And that includes healthiness.

You could look at this as a Principal / Agent problem, in that the person cooking for you may have less incentive to cook healthily than you do. However, if we’re being honest, a lot of us don’t meet the basic requirements for this problem in the first place: we don’t do a great job cooking healthily for ourselves, and often have to turn to other people in order to design and maintain a healthy diet. This, to me, is the sneaky and more worrisome problem in the long run. The more food preparation gets outsourced, the more healthy eating turns into a luxury good: something that’s an upcharge, rather than the base model.

There are two reasons for this, I think. First of all, “healthiness” is a classic sort of upcharge-y thing: it’s hard to quantify, but you also can’t put an upper bound on price so easily. Suppose a standard lunch costs $10 but a healthier salad from Sweetgreen costs $13; the category of people who are willing to pay that extra $3 would probably just as willingly pay an extra $5 or even $10 if you push them. Fully monetizing your best customers can mean pricing these premium healthy options out of reach for those with less disposable income.

Second, and I think the real driving force behind this, is that when you’re selling people food, you care a whole lot about retention: you want people to keep coming back for your food. And if you can’t do this through premium features like tasty healthiness (which can be expensive), the other cheaper way to do it is to make your food less healthy: add more fat; add more salt; make your food easier to enjoy.

This bifurcation (again with the bifurcations! It’s a theme) isn’t a good thing in my opinion. When you’re cooking food for yourself, the healthiness of the food you make is going to be a combination of many different decisions and choices you make: what ingredients you buy, what quantities you use, how you prepare your food. But when you outsource cooking as a service to someone else, healthiness increasingly becomes a yes-or-no premium option. I similarly worry that this kind of bifurcation is having similar unhealthy effects at the population level in other areas, like media for example. The internet isn’t fully destroying the journalism business model; it’s simply bifurcating it into one segment who can afford to pay for premium “healthy news”, and another segment who consumes the base “unhealthy news” option. Abundance turns Good Decisions into pay-to-play “responsible choice as a premium option”. And that’s not great.

Have you seen Toronto-based?: https://www.kitchenmate.com/

Excellent analysis. However with the IPO’s of Lyft and Uber showing us how much those companies don’t make money I wonder how feasible the it is for this to really take over?

Delivery is expensive. Maybe not as much as a front of house for a restaurant bit we are seeing that even at the massive scale of Uber and Lyft it is still a money losing venture.