A Muscular Empathy

It's easy to say you would have acted better than a slave master if you had lived in the antebellum South; or escaped poverty if you grew up in an inner city in more modern times. But it's much more interesting to assume that you wouldn't have, and then ask "Why?"

We had a lot of fun with this on Twitter last night:

The President's speech got me thinking. My kids are no smarter than similar kids their age from the inner city. My kids have it much easier than their counterparts from West Philadelphia. The world is not fair to those kids mainly because they had the misfortune of being born two miles away into a more difficult part of the world and with a skin color that makes realizing the opportunities that the President spoke about that much harder. This is a fact. In 2011. I am not a poor black kid.I am a middle aged white guy who comes from a middle class white background. So life was easier for me. But that doesn't mean that the prospects are impossible for those kids from the inner city. It doesn't mean that there are no opportunities for them. Or that the 1% control the world and the rest of us have to fight over the scraps left behind. I don't believe that. I believe that everyone in this country has a chance to succeed. Still. In 2011. Even a poor black kid in West Philadelphia. It takes brains. It takes hard work. It takes a little luck. And a little help from others. It takes the ability and the know-how to use the resources that are available. Like technology. As a person who sells and has worked with technology all my life I also know this.If I was a poor black kid I would first and most importantly work to make sure I got the best grades possible. I would make it my #1 priority to be able to read sufficiently. I wouldn't care if I was a student at the worst public middle school in the worst inner city. Even the worst have their best. And the very best students, even at the worst schools, have more opportunities. Getting good grades is the key to having more options. With good grades you can choose different, better paths. If you do poorly in school, particularly in a lousy school, you're severely limiting the limited opportunities you have.

When I read this piece I was immediately called back, as I so often am, to my days at Howard and the courses I took looking at slavery. Whenever we discussed the back-breaking conditions, the labor, the sale of family members, etc., there was always someone who asserted, roughly, "I couldn't been no slave. They'd a had to kill me!" I occasionally see a similar response here where someone will assert, with less ego, "Why didn't the slaves rebel?" More commonly you get people presiding from on high insisting that if they had lived in the antebellum South, they would have freed all of their slaves.

What all these responses have in common is a benevolent, and surely unintentional, self-aggrandizement. These are not bad people (much as I am sure Mr. Marks isn't a bad person), but they are people speaking from a gut feeling, a kind of revulsion at a situation that offends our modern morals. In the case of the observer of slavery, it is the chaining and marketing of human flesh. In the case of Mr. Marks, it's the astonishingly high levels of black poverty.

It is comforting to believe that we, through our sheer will, could transcend these bindings -- to believe that if we were slaves, our indomitable courage would have made us Frederick Douglass, or if we were slave masters, our keen morality would have made us Bobby Carter. We flatter ourselves, not out of malice, but out of instinct.

Still, we are, in the main, ordinary people living in plush times. We are smart enough to get by, responsible enough to raise a couple of kids, thrifty to sock away for a vacation, and industrious enough to keep the lights on. We like our cars. We love a good cheeseburger. We'd die without air-conditioning. In the great mass of humanity that's ever lived, we are distinguished only by our creature comforts, and we are, on the whole, mediocre.

That mediocrity is oft-exemplified by the claim that though we are unremarkable in this easy world, something about enslavement, degradation and poverty would make us exemplary. We can barely throw a left hook--but surely we would have beaten Mike Tyson.

It's all fine and good to declare that you would have freed your slaves. But it's much more interesting to assume that you wouldn't have and then ask, "Why?"Some weeks ago I met a student who was specializing in economy and theater. She said that what she loved about both fields was that she had to presume a kind of rationality in studying her actors. She had to surrender herself--her sense of what she would like to think she would do--and think more of what she might actually do given all the perils of the character's environs. It would not be enough to consider slavery, for instance, when claiming "If I was a slave I'd rebel." One would have to consider, for instance, family left behind to bear the wrath of those one would seek to rebel against. In other words, one would have to assume that for the vast majority of slaves rebellion made no sense. And then instead of declaration ("I would do..."), one would be forced into a question ("Why wouldn't I?").

This basic extension of empathy is one of the great barriers in understanding race in this country. I do not mean a soft, flattering, hand-holding empathy. I mean a muscular empathy rooted in curiosity. If you really want to understand slaves, slave masters, poor black kids, poor white kids, rich people of colors, whoever, it is essential that you first come to grips with the disturbing facts of your own mediocrity. The first rule is this--You are not extraordinary. It's all fine and good to declare that you would have freed your slaves. But it's much more interesting to assume that you wouldn't have and then ask, "Why?"

This is not an impossible task. But often we find that we have something invested in not asking "Why?" The fact that we -- and I mean all of us, black and white -- are, in our bones, no better than slave masters is chilling. The upshot of all my black nationalist study was terrifying -- give us the guns and boats and we would do the same thing. There is nothing particularly noble about black skin. And to our present business it is equally chilling to understand that the obstacles facing poor black kids can't be surmounted by an advice column.

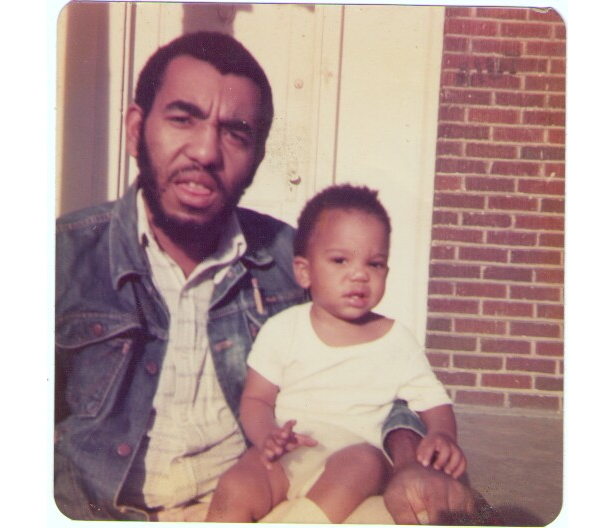

Let us not be hypothetical here. I am somewhat acquainted with a poor black kid from West Philly, and have been privileged to grapple with some of the details of his life. When he was six he came home from school and found his entire life out on the sidewalk. Eviction. He says he saw some of his stuff and immediately reversed direction out of utter humiliation. He spent the next couple of weeks living on a truck with his father, his aunt and brother. Everyday they'd search the trash for scrap to take to the yard for money. His father abused everyone in the family. He last saw his father alive when he was 9. At 17, convinced he would die if he stayed in Philly,he dropped out of high school and lied his way into a war.

You will forgive me if I've written in these pages of my father with a kind of awe. It is not merely the fact of being my father, but having acquainted myself with his childhood conditions, I shudder to think of what might have become of me.

The answers are out there. But they will not improve your self-esteem.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is a former national correspondent for The Atlantic. He is the author of The Beautiful Struggle, We Were Eight Years in Power, The Water Dancer, and Between the World and Me, which won the National Book Award for nonfiction.