This past Independence Day, several dozen bookish New Yorkers eschewed the fireworks and chose, instead, to head up to a certain apartment on the Upper East Side.

A few months earlier, Michael Seidenberg, the owner of the beloved bookstorelocated in an apartment on East 84th Street, was given an eviction notice after eight years of under-the-radar, but barely secret, bookselling. He decided to close shop by the end of July.

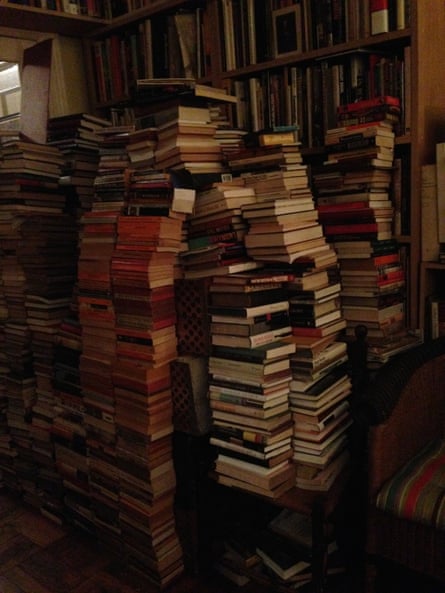

The atmosphere in the apartment put the fun in funereal. Books overflowed from ceiling-high bookshelves. Looser stacks went from floor to ceiling. Some people were still browsing and buying. But many guests held their beers and party cups of liquor, gathering around Seidenberg and his table of booze like he was the host of a wake. Seidenberg was garrulous and glowing, with a happy twinkle in his eye despite clear exhaustion. The wind-up to winding down had meant many weeks of revelry, allowing Seidenberg a chance to do what he excels at: tell stories, and hold forth on the authors and writers he loves to love.

This was actually the third bookstore Seidenberg closed. His first, which opened in 1979, was located on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn and closed in 1980. He then decamped to a storefront on 84th Street, until rising rents drove him out in 1987. Then, for about a decade, Brazenhead Books was a floating bookshop, popping up at rare book fairs and for sidewalk sales. The books were moved into the apartment after the brick-and-mortar store closed. Finally, in 2008, dispirited from the life of a roving bookseller, Seidenberg decided to open the apartment for business as a bookstore.

The shelves in Brazenhead took up every single foot of free wall space. Long stretches of fiction and essays were spiced with shorter sections of smaller, but no less meticulously collected, subjects. Seidenberg had used the standard Upper East two-bedroom apartment’s small rooms and hallways to separate his sections carefully. He still had far more books than could fit in the space. Some stacks were shoulder high, some ceiling high.

The books were also in excellent condition. Seidenberg likes first edition hardbacks and significant paperbacks and there were thousands of them: some common, some hard to find, some rare. Some were priced well below the rare book trade’s price. Others were hidden throughout the store and weren’t for sale, but seemed strategically sprinkled throughout the stacks to be noticed and coveted.

The store’s last weeks had a kind of “last days of disco” feeling, only with a certain kind of literary culture standing in for the drugs and dancing. Books often led to threads of real acquaintance. A friend picked up a copy of Raymond Kennedy’s Lulu Incognito, and then promptly fell into conversation with one of Kennedy’s former MFA students. I picked up Men and Cartoons, a collection of stories by Seidenberg’s friend and former assistant, the writer Jonathan Lethem. It had an inscription to Geoff Dyer, which read: “For Geoff Dyer, If you ever sell this book I’ll kill you.” (Yes, it was for sale.)

I asked Seidenberg about the inscription. He laughed. “It’s a joke between friends.”

Seidenberg’s approach to business is mostly as a transaction between bibliophiles. Some books he will only sell if he detects true enthusiasm from the buyer. “I’m a slow bookseller,” said Seidenberg. “I have a huge relationship to my stock.” It’s when someone finds an unusual book in his store and gets excited to buy it that Seidenberg perks up. “That kind of thing means a lot to me.” Any other person with this many books being sold exclusively out of an apartment might consider himself a rare book dealer. But Seidenberg – through his salons and a general unease with the dealer-to-dealer book trade – eschews that classification.

That night in July, I asked Seidenberg if this was really the last night of the store. He said: “I feel I can’t be trusted to answer that.”

In fact, there would end up being a few more “last nights” at the store. At another such night, despite continuing his role as enthusiastic host with aplomb, Seidenberg mentioned that too many people were coming for the booze. “I’d like to see a little more focus on the books,” he explained. The closing of the store was perhaps an opportunity to reset the bender Brazenhead was on. “People found me before and they will find me again.”

He was planning to go upstate to recover from the closure, to a house he’d bought with a small inheritance. He’d also begun to relocate the majority of the books to another apartment he actually lives in a few blocks away, and he was a little frayed after the month of seemingly endless revelry. “All I’m seeing right now is people destroying shit. It’s a failed social experiment,” he said with resignation.

Seidenberg’s concerns about his books and the people who are interested in them, or the lack of interest in them, track closely with observations made by today’s cultural critics about millennials with access to everything via the internet. Few appear not to be investors in books or writers themselves. Few are willing to do the dirty work to dig through stacks to find a writer they’ve never heard of. Few are pushing books by forgotten or rediscovered writers into their friends’ hands. Some are, but not as ravenously and obsessively as he remembers when he was their age. He wonders where the hunger is. It is curious to Seidenberg how many salons he’s hosted without selling books. “Some nights we do sell, but other nights: nothing.”

Weeks later, after Brazenhead had closed, I walked into Seidenberg’s home at his invitation. I had to do a double take. It looked as though the 84th Street apartment had picked itself up and walked down the street. The ceiling-high bookshelves had already been lined up down the front hallway and organised into the first edition section for fiction. The books now face a long wall of graffiti painted by Jonathan Lethem’s brother, Blake Lethem, a well-known graffiti artist known as Keo. Piles and boxes of books lined the floors, books piled on tables like a model of a cityscape.

I asked when he would be open for business. “We’ve had customers already,” Seidenberg answered.

The move had taken weeks. With help, Seidenberg moved 60 to 100 boxes a day, but he doesn’t know how many books he actually has. “I’d need a person with analytics to figure that out.”

I asked why he kept having the parties when it had started to damage his stock. “It didn’t seem worthwhile to ruin everyone’s parade,” he said. “But by the end there were a lot of hangers-on who were there for booze and not for books. The inner-circle people weren’t happy those last days.”

He added: “It wasn’t a good business plan.”

Yet Seidenberg is beginning to feel hopeful for the new Brazenhead. He just wants to figure out how to do it so people who are there for the scene and not the substance don’t overrun his apartment. He will return to having browsing appointments. And he will bring back the poetry nights, because, he explained: “Poets are readers.”

At one point I made the mistake of asking him what the name of his first bookstore had been. He looked aghast. “They are all Brazenhead. It’s like Spartacus,” he said, referring to the fact that though Spartacus died, his body was never found.

In the past couple of weeks, drawings and simple animations of actual red herrings, hiding clues about how to contact Seidenberg, have started appearing again on his personal Facebook page.

Whatever shape the bookstore takes in the future, Brazenhead has long been in the process of building its own mythology. It’s a tale of a bookstore that has never actually closed, but only reveals itself to the people who seek it out. Those people will be relieved to know that reports of its death have been greatly exaggerated.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion